For some of us, it’s a familiar siren call — the lure of artistic practices that help us feel connected to our cultural heritage. In this extended essay, Balamohan Shingade brings light and shade to this longing, warning of the ways that it can leave us vulnerable to its profiteers.

It is good to swim in the waters of tradition, but to sink in them is suicide.

— MK Gandhi, Navajivan, 28 June 1925

✺

Coming to the path

I began as a student of Carnatic music when my mother installed me with a teacher in Hyderabad at the age of six. When I was almost ten, our family migrated to Tāmaki Makaurau, and my training stopped abruptly.

We lived on Don Croot Street, where feijoas grew above the clothesline, and a conspicuous Telecom phone booth stood sentinel across the road. In those early days of our migration, my prized possession was a tape deck with two CDs purchased from St Luke’s shopping mall: songs by the playback singer Sonu Nigam and an album called Sifar by Lucky Ali. (It was rumoured that Ali lived incognito in the western suburbs of Tāmaki, in Henderson.) The interlude at 2:30 minutes of Ali’s ‘Dil Aise Na Samajhna’ hovered like a daydream — Hindustani tabla with Carnatic violin in a singer-songwriter’s arrangement.1 It had a strange familiarity, like a scent pulling me into the memory of something inexplicable and yet specific. I announced to my mother by the clothesline that I’d like to retake music lessons, but this time in the Hindustani stream. After some effortful years at kindling a practice with a Marathi aunty in Tāmaki, my parents sent me to Pune in 2008 to find a teacher.

My reason for taking up Hindustani music was to recover from deracination — from being uprooted from my birthplace and the context of my upbringing. But there may be other reasons for a diasporic person to take up a traditional practice, to search for a cultural inheritance. For example, it can be prompted by tangata whenua who implore tauiwi to ‘be tau (at peace) with your position.’ In her blog, Tina Ngata recounts her aunt’s words to researchers who had come to work with her community: ‘Stop trying to be Māori, I don’t need you to be Māori — I’ve got that covered. I need you to be a good treaty partner.’ This sort of a wero can be jostling for migrants of colour who arrive at the picket line in support of tino rangatiratanga or at the paepae to learn te reo and te ao Māori, but without some fluency in the stories of their own peoples. It can inspire fear and shame — or at least an embarrassment that is the same as turning up empty handed.

So we turn to devotional worship with friends in our garages and sing old songs. We form theatre groups and book clubs, or formalise our curiosity by founding charitable trusts. Or we plug into the social network. In the diaspora, we see Indian painters researching the miniature tradition, Indonesian percussionists relearning gamelan rhythms, Japanese poets experimenting with haibun. By now this is familiar to old and new migrants, because so many diaspora stories have been drawn from this well of unease.

This is not a matter of cultural revivalism, because what is specifically relevant for the diasporic context is not an erasure of culture per se, but rather contextual differences and distance. The turn to arts and cultural traditions — to the stories, signs and symbols, and to the practices shared with a people’s past — is a means with which to close the gaps in our collective self-understandings. The desire is for continuity, to be tethered to one’s own across geography and genealogy.

This essay is about the ways we may be led astray in our efforts to engage with ‘ancestral knowledges’2 in our arts and cultural practices. We should take care in our engagements with the traditions of our countries of origin, because a search for one’s own cultural inheritance can become co-opted. When even far-right movements purport to indigenise or decolonise,3 these aspirations can be rerouted to support some noxious narratives. My aim here as a sathidar — as an accompanist of artists, as a companion or accomplice — is to signpost four ways we may go off track and become derailed in our arts and cultural efforts and our engagements with tradition. Even though offering a map for the right way forward remains beyond the scope of this essay, I indicate some possibilities. But before turning to the four cautions, let me say a little more about settler society and the reasons we may be led astray.

We should take care ... a search for one’s own cultural inheritance can become co-opted.

Exploiting a vulnerability

For many Indian settlers in Aotearoa New Zealand, old and new migrants alike, the dislocation from cultural roots comprises a constant negotiation of settler identity on the one hand (what it means to be a New Zealander, tangata Tiriti, tauiwi) and diasporic identity on the other (what it means to be an Indian born in Hyderabad, to be Tamil and Maharashtrian, to be inter-caste and raised a Hindu, to marry outside my ethnic groups and to be expecting a multiracial child). Dislocation mires us in an ongoing search for self-understanding, so we draw on our inheritances. In doing so, we might also aim to recover a sense of dignity based upon the identity of being Indian — given our experiences of discrimination, which we may share in common with other non-white peoples in settler societies.

White NZ League, Citizens of the future are the children of today, Auckland, 1926

It’s now well documented that, for much of the 20th century, official policy to restrict Indian immigration to New Zealand flowed from unofficial fears about an influx of ‘the Asiatic races’, whose influence would contaminate the purity of the white race and civilisation.4 In contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand, too, that an Indian is undesirable is perpetuated by a culture of whiteness. Sometimes, Indians are barred from rental accommodation because landlords and motel operators fear the smell of Indian cuisine. Other times, the forms of prejudice are direct and aggressive, such as when Indian cab drivers and superette owners become vulnerable to violent attacks, or when Sikh men are coerced to remove their turbans, or when Muslim women have their hijabs forcibly snatched. The most horrific attack was on 15 March 2019, when a white terrorist opened fire at the Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Islamic Centre in Christchurch as Friday prayers were about to begin. India was the birth country of seven of the 51 victims.5 In that same city, about a century earlier, Klansmen posted notes under the doors of recently arrived Indian residents: ‘Beware! Ku Klux Klan is here; you are watched; warning!’6

This experience of discrimination based on Indian racial identity is exploited by certain cultural groups in settler societies that foster the political ideology of Hindutva. In the crevices of such vulnerabilities, Hindutva narratives seek to inspire a form of race pride among the Hindu-identifying diaspora. However, the pride in a Hindu identity that Hindutva seeks to instil is based on a principle of othering, intertwined with which is the seeding and circulation of Islamophobia.7 The Hindutva movement gives us a clear example of misalignment and malevolence — of how diasporic engagements with notions of tradition and ancestral knowledges are liable to be co-opted for malicious ends, leaving us worse off, morally speaking.

Founder of the Hindutva ideology VD Savarkar (centre) with the chief of the Hindutva volunteer paramilitary organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) MS Golwalkar (extreme right), 24 December 1960

What is Hindutva?

The political ideology of Hindutva was first expressed in a 1923 pamphlet by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, The Essentials of Hindutva, elaborated and republished in 1928 as Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? Savarkar’s formulation has since become the charter for a militant turn in Hindu nationalism that seeks to quarry the pluralist-secularist foundations of India and construct a Hindu rashtra (Hindu nation-state) in its place — ‘where some Indians will be more equal than others.’

While Hindutva is a different word from Hinduism, the distance between the two is a matter of persistent debate. Is Hindutva a militant form or the political face of Hinduism? Or is Hindutva as a political ideology distinct from Hinduism as a pluralistic religion? It’s not the point of this essay to bridge these understandings, but it’s important to note an interplay between these two terms. In the popular projection, Hinduism has come increasingly under the influence of Hindutva, and a conflation of the two enables Hindutva groups to claim to represent the Hindu people — the ‘real’ Indian people, in the Hindutva framework.

Since its inception in pre-independence India, the Hindutva movement has sought hegemony by attempting to construct a majority under its conception of Hindu-ness, while simultaneously marginalising, excluding and erasing diverse Indian minorities. Savarkar inaugurated a conception of Hindu-ness that persists to this day in the Hindutva imaginary — a people whose essence is constituted by the nation (rashtra), and bound together by blood (jāti) and civilisational culture (sanskriti).8

Of salience to the narrative construction of Hindutva is the othering of Muslims and Christians, who are portrayed as invaders or an internal threat to the Hindu nation. When an American war correspondent asked Savarkar in 1944, ‘How do you plan to treat Mohammedans?’ Savarkar replied, ‘As a minority, in the position of your Negroes.’9 In the present day, based on this principle of othering, the Hindutva movement attempts to mobilise the majority against alleged injustices done by the other through a combination of cultural vigilantism and violence, which is discursively framed as restoring Hindu pride — safeguarding the interests of and protecting the historically victimised Hindu.10

‘गर्व से कहो हम हिन्दू हैं! [Say it with pride, we are Hindu!]’ has long been the chant of an ascendant and assertive Hindu nationalist chorus. So when Hindutva activists demolish a sixteenth-century Indian masjid, when they intimidate a Carnatic singer because his concerts include non-Hindu songs on Jesus and Allah, when they threaten the lives and livelihoods of journalists and scientists confronting superstition, when they galvanise 3,036 people to sign petitions against academic freedoms of New Zealand-based scholars, they claim to restore Hindu pride.

Combined Threat Assessment Group, Threat Insight: Hindutva Violent Extremism in New Zealand, 8 April 2021

Interfering in our togetherness

Indian New Zealanders are a diverse group,11 with communities intermingled across ethno-linguistic and religious lines.12 But contemporary experiences of togetherness across difference are threatened in Aotearoa New Zealand by the ascendant Hindutva movement.

Worrying about the divisiveness of this movement, human-rights activist and founder of the Inclusive Aotearoa Collective Anjum Rahman gives examples of dehumanising speech directed against Muslims in Aotearoa New Zealand by Hindutva-aligned groups and individuals. From about 2014–21, the ‘Indians in New Zealand’ Facebook group, with over 100,000 members, became a forum where group administrators would post Hindutva propaganda and hateful comments against Muslims, and then adjust the settings to suspend commenting rights for anyone who challenged them. The page was crowded with abusive language and slurs, dehumanising discussions that ridiculed hijabi women, memes that framed Muslims as terrorists, representations of India as a Hindu deity fighting against Muslim threat, and conspiracies that blamed the spread of Coronavirus on India’s Muslims. ‘Each one of these comments in and of itself is bad … but the issue is when there’s so much. And there was so much material.’ Many of the people posting were identifiable by name, and included registered financial advisors, political candidates and city councillors in Aotearoa.

Such inflammatory speech is part of the Hindutva movement’s routine discourse to justify threats of violence against Muslims. In the wake of the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings, it is vital to critically interrogate how Islamophobia flows through various ideological formations, including white supremacy and Hindutva.

An appropriate pressure

Given the detrimental effects of Hindutva on minoritised and marginalised communities, it is then necessary for artists to clarify their position if they choose to work with the signs and symbols and stories that the supremacist movement also uses for its promotion. For example:

- songs and slogans in praise of Rama;

- the colour saffron and the lotus flower;

- Sanskrit as ‘the chosen means of expression and preservation,’13 especially when favoured over regional languages;

- Hindu temples in place of civic or community centres;

- no-onion-garlic vegetarianism over customary beef dishes;

- Diwali in the diaspora instead of an all-India festival;

- the worship of Vishnu rather than King Bali;

- the saffron-washing of fakirs such as Shirdi Sai;

- language schools and cultural programmes with stories that promote India as a cradle for self-realisation and salvation, a land of Vedas and sutras taken as the origin of all intellectual and scientific discoveries, yoga and puja, an ancient civilisational culture that is supposedly under threat.

But clarifying our position is, in itself, not enough. Since Hindutva is the hegemonic cultural ideology of our time, it’s possible to represent it unknowingly while at the same time purporting to be against it. In order to be fully morally responsible, we must have an awareness of and an association with communities who are detrimentally affected by the movement. The clarity of our position is the first step towards accountability to others, and to ultimately de-legitimising the ideology.

✺

FOUR CAUTIONS

Prime Minister Narendra Modi pays tribute to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, 2014

1. Injured pride

There is a cost to the human spirit exacted by perpetual experiences of racism and resistance, which Hindutva ideologues promise to repay with the currency of pride.14 Todd Nachowitz’s doctoral thesis on the Indian diaspora in Aotearoa New Zealand makes clear the practical use of pride:

Having a sense of ethnic pride, being involved in and demonstrating a commitment for the sociocultural and religious activities and practices of one’s particular ethnicity, can be a strong coping strategy for migrants experiencing discrimination and racism in their adopted homeland.15

Nachowitz’s phrase ‘coping strategy’ is well chosen, because pride does not seek to directly overcome the injustices. Pride is actually a misfiring effort at recovering from racial prejudice and persistent discrimination.16 In fact, it ends up reproducing or embedding the wrong it seeks to overcome, because to ‘cope with’ is to continue allowing; it’s to keep the wound open. Coping accommodates rather than resists racism.

In several of the Indian philosophical traditions, the core of pride is identified as a type of narcissistic self-preoccupation. For example, the Sanskrit term ‘abhimāna’, from Hindu thought, translates to a concept of pride as ‘selfish conviction’, or self-attachment based on excessive self-thought, including identifying with and interpreting phenomenal experience as a function of the self.17 In some Western traditions, too, self-absorption is at the core of pride. As in Dante Alighieri’s image of the proud in Purgatorio — figures bent in on themselves like hoops, who look only at themselves — the proud fail to acknowledge the humanity of others. Famously, David Hume gives the example of the ‘master of the feast’, where the guests may all feel joy, but only the master feels ‘the additional passion of self-applause and vanity.’18 He takes an interest in the feast not for its own sake but for prestige and position, and so the upswell of prideful emotion comes from that core of narcissistic preoccupation.

What is it that the Hindutva ideologues insist that the diaspora take pride in? The cultural narratives of Hindutva invite an overseas Indian Hindu to inhabit a worldview of — and belong to a people sharing — civilisational greatness, ethno-religious superiority, and a purity of culture that is allegedly threatened by the other. The claim is to a continuity of the culture and tradition of a majority population historically found in the subcontinent that goes back more than 3,000 years, or at least to the Vedas.

Daniel Villafruela, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh youth parade, Udaipur, 2013

The Hindutva movement has been preoccupied with pride, and with the instilment of this character trait, from its beginnings. In his 1939 book We or Our Nationhood Defined, MS Golwalkar wrote:

German race pride has now become the topic of the day. To keep up the purity of the Race and its culture, Germany shocked the world by purging the country of the Semitic Races — the Jews. … a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit by.19

In a 1939 address to members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindutva volunteer paramilitary organisation, Golwalkar asserted, ‘If we Hindus grow stronger, in time Muslim friends … will have to play the part of German Jews.’20 In this way, Hindutva seeded Islamophobia at the root of Hindu pride. Pride as a character trait continues to be intertwined with the construction of a Hindu people who have had their pride injured, and have been made prideless, servile and weak by Muslims and Christians. In retribution, Savarkar appealed to Hindus to disavow soft values, such as ‘humility, self-surrender and forgiveness’, and nurture ‘sturdy habits of hatred, retaliation, vindictiveness.’21

Instead of resisting the nuts and bolts of colonial domination through policy and positive visions for home rule, Hindutva idealogues rearticulate injustice in the framework of pride, shame and offence. In other words, Hindutva mandates that we ought to recover not from the injustice of colonialism, but rather the shame of being colonised.22

Pride makes us focus on the wrong things. We mustn’t let pride or shame be the basis for our efforts at engaging with ancestral knowledges, because this narcissistic character trait redirects our concerns to optics and looking good. We become preoccupied with our self-image, our appearance in the marketplace as artists, rather than looking for resources with which to turn to our present. When we care more for the reputation than the relevance of our traditions for facing matters of justice, then they’re no longer alive — it is a sign that we have ossified them. Stories and symbols begin to float untethered from the way that people’s lives actually go.

Hindutva mandates that we ought to recover not from the injustice of colonialism, but rather the shame of being colonised.

2. Cultural essentialism

The internet was ablaze with accusations of cultural appropriation when Beyoncé starred as a bejewelled Bollywood bride in Coldplay’s 2015 music video ‘Hymn for the Weekend’. Tweeters pounced on the imprecision and incomplete adornment, the apparent commodification of ceremonial dress, and the waft of a stereotypical and unduly exoticised portrayal of Indian custom.

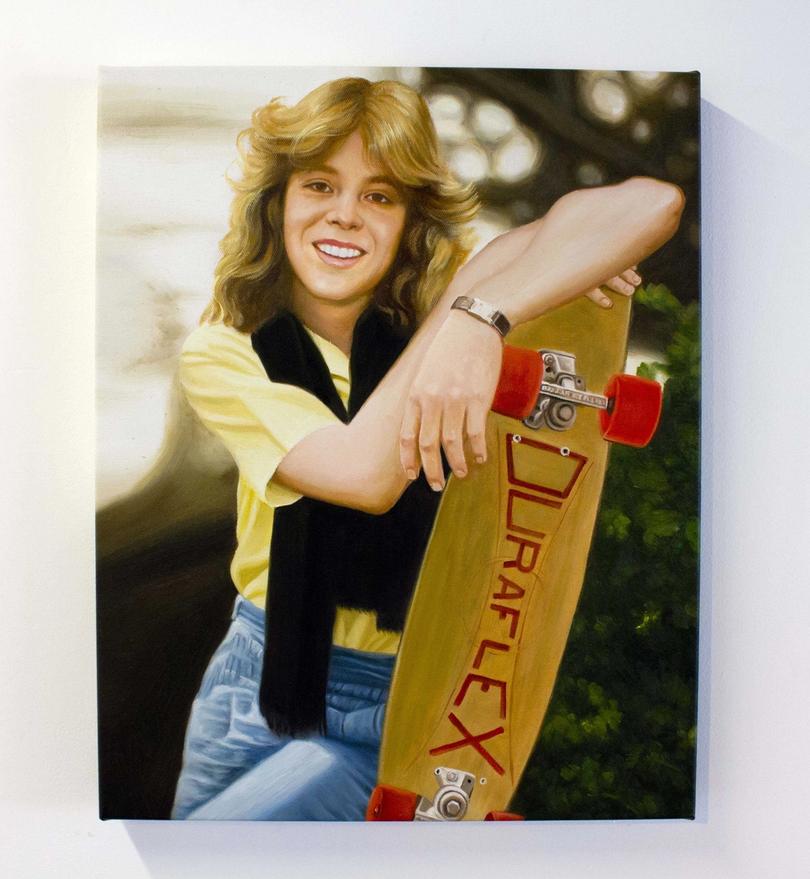

During this time, Bepen Bhana was in the mix as an artist and a careful observer of pop culture. His exhibition Hey Bey (2017), which featured dizzying paintings of Beyoncé, attended to this moment of hysteria to study competing claims of cultural appropriation and cultural hybridity. Bhana’s art traffics in such mixing up of identities, but it’s usually difficult to render in black and white his position on the debate — a commitment to complexity that is worth unpacking.

Bepen Bhana, Hey Bey - Hymn For The Weak End (Suite II, Number III), oil on canvas, 2017

We’re probably familiar with cultural outsiders and non-members being charged with appropriation. The moral issue usually hangs on the misrepresentation of stories, signs and symbols, or the misuse of the materials of a historically oppressed people. When it comes to music, we might wonder whether it was permissible for George Harrison to play the sitar on his records, and whether it was right for him to profit when he was only a beginner student of Hindustani music.

When I was in India for my fourth Hindustani music residence in 2018, the Carnatic singer TM Krishna was a target of online abuse and offline hate by adherents of Hindutva for including non-Hindu songs in his concerts — songs about Jesus in Malayalam and Allah in Tamil, verses by 12th-century philosopher Basava and 21st-century author Perumal Murugan, and bhajans by anti-colonialist Gandhi and poet-sant Tukaram. Hindutva activists harassed Krishna’s concert organisers until these performances of Indian pluralism were called off.

Anything that is considered ancestral to India is a site of contestation for the Hindutva movement. Since Carnatic and Hindustani music market and sustain themselves by being among India’s classical arts and cultural traditions, they risk becoming co-opted by Hindu nationalists. It is an insidious form of appropriation from within the Indian community. These exercises of coercion and gatekeeping by Hindutva activists take the guise of protecting the purity of a victimised culture.23

The Hindutva appropriation is based on a claim about culture as an essence — the idea that enduring features or unchanging core characteristics define Indian-ness as Hindu-ness. In this view, Hindu-ness is natural and necessary, rather than constructed and contingent. Hindustani and Carnatic traditions are characterised as the cache of the Hindus, traceable back to a mythic Hindu civilisation. Crucially, in their project to ‘make India Hindu again’, non-Hindu claims upon Indian traditions are figured as invasive.

Unknown photographer, Babri Masjid, Faizabad, c. 1863–87

The truth remains that Hindustani music, and many of India’s classical arts and cultural traditions, does not belong to Hinduism as a religion, let alone Hindutva as a political ideology. Centuries of Muslim artists risk being invisibilised in the present-day de-Islamisation under Hindutva — branded as decolonisation by the Hindutva movement. The movement’s end goal is the exclusion and erasure of diverse groups who have legitimate claims to India’s arts as its co-authors. This form of co-option is the inverse to appropriation by cultural others, and perhaps more damaging in the way it flies under the radar in multiculturalist diaspora contexts.

Working with ancestral knowledges can’t be limited to simple rehearsals of dominant narratives. The impulse to trade on essentialist characterisations of culture ought to be rejected, because it is not a monolith. Culture-making is a site of power to transform our collective ways of knowing and relating. It is a creative act wherein exclusions and erasures can easily be perpetuated, and in our roles as artists we have a choice either to be alert or unaware when certain groups are written out of a narrative. In our engagements with ancestral knowledges, we can redress their past and present prejudices and seek alignment with egalitarian commitments: anti-caste and anti-class struggles, for feminist futures and in solidarity with queer peoples.

Tradition must be forward looking, future oriented. We need to connect the desire for ancestral knowledges with our aspirations for a future world that is better. Rather than a set of inflexible, unchanging rules, or hollowed-out markers for self-design and promotion, we should take tradition as a studied resource with which to turn to our present and to orient ourselves to matters of justice. We should strive to live by the assessments of future generations, rather than worry about the approval of our ancestors.

We need to connect the desire for ancestral knowledges with our aspirations for a future world that is better.

George Harrison studying the sitar with Pandit Ravi Shankar, probably 1968

3. Re-orientalism

When I returned from my routine residencies in India and began performing Hindustani music in Tāmaki Makaurau, among my first listeners were recovering orientalists. I still remember a concert from 2010 with some amusement: I was accompanying my teacher Pandit Rajendra Kandalgaonkar on his first tour of Australasia. By now, I was an undergraduate student at Elam School of Fine Arts, and dotted amongst the audience in Tāmaki were a few Pākehā artists from the contemporary scene. In anticipation of a concert that would offer heightened spiritual experiences, some of them had taken magic mushrooms beforehand.

It’s not the mixing of gigs and drugs that I want to note, but the exoticism circulating in the dominant culture that sets the expectation that a traditional Indian art form will offer transcendence. (It might! But it might not.) Either way, it is an orientalising hangover from Merchant Ivory Productions and the Beatles–Pandit Ravi Shankar era that many Pākehā are still recovering from.

Here was my ready audience — a marketing opportunity. And it would have been easy to set up a stall to transact on the promise of ecstatic experiences, to become a dealer in the exotic arts and quite literally ‘play to the gallery’ of outsider audiences with cartoon knowledge of Indian cultures. Ornamenting the backdrop of whiteness with non-Western art can be an alluring prospect. It can be a pathway to prosperity, and many painters and performers alike have built highways here to progress their careers. But under the scrutiny of an audience steeped in these traditions, whose lives continue to be bound up in them, such forays are trinkets and tinsels.

My point is not to disparage diasporic artists, nor do I wish to set up a dichotomy between Indian and non-Indian audiences, or those living in India and abroad. The discrepancy between these groups is not the issue, because diasporic artists naturally have different issues and insecurities in order to make sense of our hyphenated lives and the plurality of our attachments and allegiances.

My concern is that we risk ‘othering’ ourselves. I worry that we consign Indian-ness to otherness through our artistic practices, that we make work disassociated from the very real ways in which people’s lives actually go, from the conceptual and aesthetic rigours of our inheritances. More specifically, I worry about the emergence of a new category of orientalists from among the Indian diaspora who themselves engage in a form of self-exoticism — and find an eager audience. Lisa Lau is a human geographer who identifies this tendency in her study of English literature by some writers of the South Asian diaspora. She calls it ‘re-orientalism’.24

... it would have been easy to set up a stall to transact on the promise of ecstatic experiences, to become a dealer in the exotic arts ...

Screenshot of former Labour MP Gaurav Sharma taking an oath in Sanskrit in the New Zealand Parliament, 25 November 2022

If orientalism, according to philosopher Edward Said, is a practice of exoticising the East from an external point of view, then re-orientalism describes self-exoticism — the perpetual consigning of Indian-ness to otherness from an internal perspective by a people who claim to represent themselves and their social groups. Of course, even at the time he was writing, Said noted that not all orientalists are Westerners and the consent of the so-called Orientals is necessary to the practice. But widespread re-orientalism as identified by Lau appears to be new.

As Indian artists, we may reference mangoes and paisleys, we may draw esoteric things and use Sanskrit to explain our efforts, we may bring yoga and meditation into theatre structures. It’s a nostalgia that looks towards something fantastical, not unlike the references to Indian-ness made by outsiders — The Third Eye on Karangahape Road, or music festivals awash with baggy elephant pants and incense sticks.

Lau gives the example of The Mango Season (2003), a novel by Amulya Malladi about a 27-year-old Indian expatriate named Priya who’s been studying and working in the United States. Her worried parents in Andhra Pradesh have arranged her marriage with a Telugu Brahmin, so Priya dreads this return trip to India wherein she must confront them with the news of her engagement back in San Francisco to an African American man named Nick.

The sensationalisation of Priya’s defiance in this novel only works because of Malladi’s projection of Indian backwardness. As Lau says, ‘The entire story and the life of the protagonist is apparently centred around the fact that she is Indian, with all the non-negotiable cultural baggage that being an Indian girl is made out to bring.’25 In the first page of the novel’s prologue: ‘Even though I was raised in a society where arranged marriage was the norm, I always thought it was barbaric to expect a girl of maybe twenty-one years to marry a man she knew even less than the milkman.’ Malladi’s persistent need to explain cultural norms through her characters is revealing of re-orientalism. The novelist seems anxious that she and her story be read as recognisably Indian to outsider readers who don’t understand the ins and outs of Indian cultural norms. But ‘playing to the gallery’ is not the only thing that makes the novel a case study of this tendency for Lau.

In casting ‘Indian culture’ as the locus of conflict in her story, Malladi erases powerful examples of feminist organising in India that intervene in practices such as endogamy.26 The novel demonstrates the blinkered perspectives of the upper castes, for whom moving to the West is taken as synonymous with upward mobility and social freedom. Malladi shows a lack of respect and knowledge of the vernacular contexts that she is claiming to represent, while at the same time hollowing ‘Indian culture’ of its substance to create a flat-packed product.

Re-orientalism begins with an unfulfilled human need: against the backdrop of racism, there is a need for shared self-understanding and recognition as an Indian. But the incentive structures that promote arts and cultural practices in settler societies are generally averse to complex and layered perspectives. Negotiating the dominant culture on the one hand and market logics on the other, that basic human need can quickly turn to commodifiable points of difference. Exoticism is traded for a greater share in the pool of resources and the economy of attention.

The problem is that re-orientalism prevents accurate and ethical understandings. It is a wrong we do to ourselves in our capacities as knowers and knowledge holders. Re-orientalism can produce a form of self-alienation. By limiting the scope of our artistic enquiries and our interest in the complexity of our cultural inheritances, we risk remaking our sense of self in favour of marketable appearances. We risk mistaking ourselves for what the dominant culture says about us. We risk becoming strange and estranged.

It is a specific kind of challenge, then, that Indian diaspora artists must negotiate in our efforts to anchor ourselves in ancestral knowledges. We primarily require a sensitivity to questions of power and the asymmetrical relations we’re enmeshed within. We need to be dry-eyed about the fact that the truth is frequently less exotic but more interesting than the flattened discourses that Indians can construct through re-orientalism. For example, the historical record shows us that there isn’t anything so mystical in Indian thought that doesn’t also appear in the history of Western thought, and there isn’t anything so rational in the West that doesn’t also have precedence in India.27 Yet contemporary prejudices inculcate in us a belief of India as a cradle for self-realisation and salvation, and that our cultural prerogative is to represent this to our audiences, who’ve come, in fact, to expect this of us.

Re-orientalism can produce a form of self-alienation. ... we risk remaking our sense of self in favour of marketable appearances.

Photograph taken during the Odeon recording sessions of December 1936. Seated: Ustad Abdul Karim Khan. Left to right: R. D. Sethna (Ruby Record Co.), Shamsuddin Khan, Dashrath Mule, Balkrishna Kapileshwari, Harishankar Kapileshwari, Max Birckhahn (recording engineer)

4. Empowering subjection

There are stories of students whose search for a teacher takes them on intrepid travels. My teacher’s teacher, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, ran away from home at the age of 11 to seek an education in music after hearing Ustad Abdul Karim Khan crackle through a gramophone. Meeting my own teacher was thankfully uncomplicated. I was introduced to Pandit Rajendra Kandalgaonkar in Pune by the Marathi aunty from Tāmaki.

I’d meet Guruji for lessons at the music college he headed, or he’d visit me at the apartment. We’d speak only of music. And if we spoke about anything else, it was always in light of how it gets in the way of music — administration for the college, interpersonal rifts, egos and personalities … all of it burdensome for the path of a musician, for whether or not we’re able to sustain our practice. In this very ordinary way, I entered into the guru–shishya parampara — the teacher–student system or master–disciple tradition.

The poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore evokes the image of a candle for an ideal guru, because a candle must consume itself in order to light the way for others. At its best, the guru–shishya system is a site of transformative education, especially if the guru is compassionate and accomplished, like mine is. But the risk of this system is that the possibility of an education depends too much on the disposition of the teacher. I am lucky, but to make proper learning a matter of good fortune seems unfortunate. From teacher to teacher, behavioural norms and expectations can vary, and in a fundamentally asymmetrical relationship that’s absent of broader structures of accountability, it becomes difficult to remedy misuses of power or even to reconcile a mismatch of values.

At its worst, the economy of the master–disciple tradition is sustained by the student’s subservience. It’s vulnerable to inegalitarian logics, placing the student in a mode of cyclical indebtedness. Sometimes the godliness bestowed upon the guru insulates them from the petitions of a shishya when things go wrong, such as in 2020, when a student of high-profile singers the Gundecha Brothers posted on Facebook about sexual harassment. Surprisingly, it was not the Gundecha Brothers but the student who was accused of defiling the sanctity of the guru–shishya parampara. She was maligned for tarnishing the reputation of the revered gurus and had to face doting shishyas adjudicating the case in their gurus’ favour through ‘a social media trial in the comments section.’28

Relational commitment is often said to help us avoid the many pitfalls of re-orientalism, cultural appropriation, deracination, and so on. This is in part true; we need to be anchored in the communities whose lives are bound up with the substance of our arts and cultural practices. However, the structure of those relationships matters — who they’re with, the networks they’re embedded within, the norms and expectations they circulate, etc. Relationships often lay down the material and motivational tracks for our practices — i.e., our capacities and our reasons for sustaining them. But sometimes, instead of offering an artist a meaningful context and appropriate checks and balances, relationships themselves can end up subjugating artists and assigning them to regressive attachments and allegiances. The guru–shishya tradition is an example of a personal, one-to-one relationship, but equally worth examining is how we stand in relation to larger groups and social-political movements.

But sometimes ... relationships themselves can end up subjugating artists and assigning them to regressive attachments and allegiances.

Portraits of Hindutva ideologues (K. B. Hedgewar, Lakshmibai Kelkar, and M. S. Golwalkar) with garlands at HSSNZ’s shakha (branch), shared on HSSNZ’s public Facebook page, 2018

At the same time as I was entering Hindustani music in the mid-2000s, some diasporic children in Tāmaki Makaurau, also searching for a cultural inheritance, were enlisted by their Hindu parents in Hindutva-affiliated organisations for language learning and religious observances. These organisations were the predominant structures available to anxious parents and children, and it’s where we see most clearly the insufficiency of relational commitment vis-à-vis matters of justice, culture and politics.

The present-day Hindutva movement is organised as a network of paramilitary volunteers, civil society and cultural groups, religious institutions and political parties, referred to collectively as the Sangh Parivar (‘the family of Sangh’ — i.e., of the volunteer paramilitary organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh [RSS]).29 The Indian RSS provides ideological enculturation as well as weapons training, especially through the Sangh Shiksha Varg camps for youth (Sangh training for troops). The pedagogical structure of the RSS is reproduced outside of India by several Sangh-affiliated groups, such as the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (Hindu Volunteers Corps).30 The HSS in New Zealand (HSSNZ) promotes the Sangh Shiksha Varg camp in this country as a way that parents may ensure their children growing up in the diaspora are proud of their heritage.

Using cultural programmes as the basis for pedagogy, the HSSNZ responds directly to migrants’ anxieties of deracination and experiences of discrimination. For example, the HSSNZ’s Sangh Shiksha Varg camp held in Tāmaki Makaurau in April 2019 incorporated marching and martial training to effectively use a lathi (a long, heavy baton made of bamboo), discussions to re-form ideological beliefs, and emotional veneration with ceremonial prostrations and garlanding of major Hindutva ideologues, including VD Savarkar, KB Hedgewar, Lakshmibai Kelkar and MS Golwalkar.31

The philosopher Arash Abizadeh uses the term ‘empowering subjection’ to describe how being-in-relation can simultaneously be empowering and disempowering.32 On the one hand, being-in-relation can afford collective power — enhancing one’s power with others to effect desired outcomes; to be rewarded with patronage, a sense of community, an experience of solidarity, and so on. On the other hand, it can diminish one’s agential power because exiting from such social relations can be costly, incurring loss of opportunities and ostracisation. The Hindutva network is particularly effective at sustaining mass clientelism through a coercive regulation of social interactions.

Relationships that are absent of a commitment to egalitarian justice risk undesirable forms of empowering subjection. We need our communities to be oriented to how the lives of those detrimentally affected and the least well-off actually go. In the case of arts and cultural practice, it means an attentiveness to the exclusions and marginalisations perpetuated in the name of representation. Against the backdrop of Hindutva, we ought to turn to the voices of Indian Muslim communities, of Dalit-run organisations, of Adivasi groups, of the Indian Left, of gender-diverse peoples, of Hindus against Hindutva, and all others who experience its deleterious effects in different ways. We ought to build, through our arts and cultural practices, infrastructures of listening.

✺

The space left behind

Moving forward requires us to critically interrogate how processes of marginalisation and exclusions are perpetuated. What matters is not only that artistic traditions should be continued, but whether others have the possibility to participate, practise and perform.

In a video interview, TM Krishna unravels the social backdrop against which Carnatic music functions: ‘Who is the community? … It’s [the community] framing sound, beauty, correctness and morality. This is entirely a political statement.’ As a privileged insider in the Carnatic tradition, Krishna grapples with inegalitarianism within this insular Brahmin world. Critically reflecting on the dimensions of caste, gender and religion, he concludes that music is inseparable from the social world it’s born out of, a world in which our tastes are entirely political.

Krishna wishes to see a Dalit perform in the sabhas one day and win a Sangeetha Kalanidhi title.33 For his own part, he responds by exiting concert halls and taking the music to the everyday lives of diverse communities. He sings with the transgender Jogappa communities from the South; he vows to release one Carnatic song a month on Jesus or Allah in defiance of Hindutva groups’ efforts at silencing him; he takes a Tamil swear word as the refrain for a song and ornaments it in classical intonations to protest against environmental destruction in Chennai. And in return, he is accused by the upper castes of polluting ancestral knowledge and defiling tradition.

Print of Raja Ravi Varma’s painting of Sant Tukaram distributed before 1945 by Anant Shivaji Desai, Ravi Varma Press, Baroda Art Gallery

For those of us who turn to artistic practices shared with a people’s past, who weave in and out of their originating contexts, we could pose a set of questions to guide our artistic inquiries:

- How are ancestral knowledges portrayed in ways that invisibilise, marginalise or exclude? In the name of a tradition, what and who is erased? How are arts and cultural practice configured so as to allow participation from some and disallow it from others? Conversely, to whom are the stories and structures helpful?

- What is our location within circuits of power and the spaces we occupy? What forms of power do these spaces hold, and what forms of power do we hold? How do we enact this power in relationships and in communities?

- These days, when notions of ancestral knowledge and cultural tradition are often held hostage in the wheelhouse of neo-conservatives, how do we navigate our complex pasts?

On the one hand, we may become defensive and play ostrich; we may bury our heads in the sand, resist learning more about ideology and its intertwining with arts and culture, and insist upon our innocence. We may forget about Indian-ness, treat the whole thing as volatile, and turn to the comforts of American singer-songwriters rather than Hindustani singers — let alone the music of the Jogappas, Manganiyars, Bihus. On the other hand, we might continue to work in a ‘third culture’ space but say nothing at all about our artistic uses of stories, signs and symbols that are vulnerable to complicity and co-option. We could even have our work championed by neo-conservative or supremacist movements, or turned into an advertisement for their cause.

Whether knee-jerk or calculated, reactions of both retreat and ignorance are insufficient. To disengage from our cultural inheritances is to give up on ourselves — to give up making sense of causes and conditions, and of arriving at collective ethical self-understandings.

In chess, there’s an idea called ‘the space left behind.’ Imagine a knight that moves away from the centre, or a bishop that cuts a diagonal to the other side of the board, or a queen that leaves her post. Chess players are always attentive to gaps in their position, empty squares on the board created by the movement of their pieces.

The risk with disengaging from our collective past and present is that we leave that space open to forces of dogmatism. In our own lives and our arts practices, we risk giving over the study of our cultural and religious pasts to a few scary forces. The gaps we create are hermeneutical — vacant lots in our interpretations and understandings.

We see this in the context of the United States, where sinister ethno-nationalist movements occupy Christian spaces, controlling interpretations and understandings of what is actually a transnational religion. We see this in the way Israel’s state-sponsored terrorism claims Judaism. In the context of the Indian subcontinent, a supremacist force with deep pockets, paramilitary volunteers, cultural groups and political parties has come to occupy the spaces of Hinduism, of what is a pluralistic religion. Similar struggles abound for fundamentalist Islam, militant Buddhism and others.

India Post, commemorative stamp for the death centenary of Savitribai Phule, 10 March 1998

But our disenchantment with the sphere of cultural tradition, religion and spirituality means that we overlook, forgo, and even erase those who’ve registered social-political resistance from within such spaces. Dissenters, reformers and critical thinkers have always formed a part of tradition-based inquiry.

Recall Jnaneshwar, the 13th century Marathi poet, who bemoaned the great injustices of caste, and whose own teachings tried to form a kind of spiritual egalitarianism. In the modern period, my teacher’s teacher’s teacher’s teacher, Ustad Abdul Karim Khan, was criticised by Hindus and Muslims alike for reciting the Gayatri mantra, educating Hindu students and women, and for working with an English musicologist. Even in Khan sahib’s days, attempts were made to split Hindu and Muslim communities, but they were largely unsuccessful. Efforts to vitiate this tradition failed in pre-independence India when resistance disallowed such a project as Hindutva to reach hegemonic proportions. Khan sahib’s lesson is to let the practice itself be the proof of pluralism — not just reasoned argument, but singing with practical intent to disprove the thesis of separatism and sectarianism.

To disengage from our cultural inheritances is to give up on ourselves — to give up making sense of causes and conditions ...

Progression towards social justice, or cultural and religious freedom, is not a given. We cannot rely on the notion of a better future arriving at our doors without effort. If the price of freedom is vigilance, then it’s incumbent upon us as artists to sift through these complex terrains.

In looking for resources with which to turn to the present, we might find figures of women’s emancipation in the 12th-century poet Mahadeviyakka or 19th-century educationist Savitribai Phule, religious dissenters such as Sant Kabir in the 15th century, anti-caste activists such as Sant Tukaram in the 17th century or BR Ambedkar and Periyar in the 20th, syncretic systems of the ganga-jamuni tehzeeb, interfaith councils beginning in the 3rd century BCE, and an Indian argumentative tradition dating back several millennia.

In reading the words of each, we become intimate with such critical thinkers and their struggles of the past, allowing ourselves an inheritance.