Playwright Nathan Joe surveys the development of Asian theatre in Aotearoa, going in search of a canon and discovering that the loose, nebulous edges are just as compelling.

INTRODUCTION: THE I IN ASIAN

I. PĀKEHĀ EYES: Late 1980s to early 1990s

II. FLYING SOLO: 1990s

III. THE NEED FOR COMMUNITY: 2000s

IV. A SCENE EMERGES: 2010s

V. PRESENT DECADE: 2020s

VI. FIELD NOTES FOR THE FUTURE

❉

INTRODUCTION: THE I IN ASIAN

When I first stepped into the world of theatre, I was relatively naive to the short but rich history that had come before me. Like any person with a poor understanding of the past, I made assumptions about my own place in the ecology. I bemoaned a lack of representation without an understanding of what actually existed or why certain things were the way they were. Or I celebrated the success of my friends and peers as if they were the first to ever achieve something. I was at the centre of my experience, and therefore I was limited by how little I knew.

Writer Hana Burgess says, ‘By being in good relation through whakapapa, we can know how something came to be, how it relates to wider existence, and how it will come to be.’

One might say this essay is an attempt to make sense of what I now know. To write the essay I myself would have found useful when I first stepped foot into theatre. To map the developments in Asian New Zealand or Asian Aotearoa theatre history.

It’s important, then, to set some context for this, to make my own position clear:

- I was born in 1991 in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

- My parents are both Chinese, with Dad being born in Palmerston North and Mum being a first-generation immigrant from Taishan, China.

- I can only write and read in English, and speak only the bare minimum of Cantonese.

- I am a cis-gendered, gay male.

- I am part of this history, in that my primary creative practice is playwriting (amongst other theatre-making habits).

In 2009, during my final year of high school, our head of drama selected Thoroughly Modern Millie JR. as the (bi-annual) high school musical production1 — an extraordinary choice because it featured two Chinese parts. I remember the genuine shock in seeing this opportunity come up. And that’s what it felt like, an opportunity. I remember four of us Chinese students auditioning for the two possible roles of Ching Ho and Bun Foo. Chinese-sounding names of Chinese-seeming characters. Any red flags were overshadowed by a sense of excitement and possibility. This was, after all, the same era in which Harry Potter’s infamously named Cho Chang barely warranted the raise of eyebrows. So I auditioned and got the role of bashful Ching Ho, and someone in the year below me got the role of Bun Foo. In the setting of 1920s New York City, we were two Chinese immigrants working as henchmen for a kidnapping ring.

Nathan (right) playing the role of Ching Ho in Thoroughly Modern Millie JR., 2009

Looking back, I think we were pretty stoked to have a production that might represent us, while simultaneously baffled by the existence of this musical and these characters. The model minority welcoming this opportunity with gratitude mixed with discomfort. The musical’s plot hinged on some screwball comedy around human trafficking amidst orientalist tropes. It didn’t occur to us this might be an act of self-orientalisation, two whitewashed bananas playing our FOB counterparts, cosplaying the most socially acceptable form of yellow face (performed by yellow faces). In the early 2000s, audiences laughing at Asian accents in the media was seen as a form of success. To be laughed at was, at least, to be perceived and seen, to be made visible.

When you’re starved enough, any crumb feels like a feast.

So, theatre, particularly the Western tradition of theatre, always felt like a fraught place to look for representation. A foolish or impossible mission when I just wanted the freedom to tell stories. But, even if representation was not the reason I got into theatre, I found it anyway.

When I search back through the haze of my mental Rolodex, the year 2013 remains a significant one, just after I moved up to Tāmaki Makaurau. At the time, I was overwhelmed by the options of both professional and independent theatre. Here, I encountered my first Asian New Zealand theatre shows. While these shows were exceptions rather than the rule in Tāmaki Makaurau at this time, I was still completely blown away as someone who had never seen a single Asian performer on stage before. It seemed like a luxury.

I found myself drawn to what little existed of this Asian theatre scene. I felt the push and pull of it, resisting it and at times embracing it.

My own relationship to Asian theatre-making was more complicated. I sincerely attempted to write my first play, Flesh off the Boat2 — an ‘Asian play’ — in 2013, which resulted in a one-day workshop with actors and a director. It turned out I would be the only Asian in the room. Times were very different back then. This resulted in a newfound self-consciousness with being an Asian playwright, and I decided to park the play, waiting another six years before I actually staged anything akin to an ‘Asian play’. Instead, I wrote mostly neutral plays. I wanted to be a neutral writer. Universal, even.

Despite all this, I found myself drawn to what little existed of this Asian theatre scene. I felt the push and pull of it, resisting it and at times embracing it. And, ultimately, falling in love with it.

The story of Asian New Zealand theatre history is one of not fitting in, of a tension between unbelonging and a belonging quietly fought for. Like any classic tale, it is an underdog story. It is a story of carving out a space on your own terms. Of telling your own story, otherwise someone else will tell it for you. It is ultimately a search for representation, and all the pitfalls that come with that. Pitfalls that would pop up time and time again across the decades.

I have been alive longer than a documented Asian theatre scene has existed in Aotearoa. Isn’t that extraordinary? Isn’t that shocking?

At the time of writing this, I am 33 years old. I have been alive longer than a documented Asian theatre scene has existed in Aotearoa. Isn’t that extraordinary? Isn’t that shocking? To think of an arts and culture movement as in its infancy. To think of it as something still finding its legs, only just learning to walk, only beginning to run.

I hope to make some sort of sense out of the often poorly told history of our Asian theatre culture, to reflect that there are patterns and developments, even if they are often scrambled, that each moment has made the next moment possible. This essay, which inevitably mingles the personal with the historical, is a mapping of trends and tendencies over the last 30 years or so. To chart the developments of Asian theatre in Aotearoa is to chart a sometimes-linear accumulation of milestones, while also noticing the exceptions and digressions.

As I dive into the developments within Asian theatre in Aotearoa, I am confronted by the porousness of this term, ‘theatre’. More often than not I will be defining theatre as something for a stage or space, something that fills that space with a performance. Let’s say the performance is the main reason you are in that space. Let’s say it’s scripted or devised, but has some sort of premeditated structure in place. Often when I talk about theatre, I will be referring to plays, but will not be strictly limiting myself to those. ‘Asian’ theatre further complicates this. While my first instinct is to centre works that explicitly feature Asian characters and narratives, this is admittedly a rigid measure. In the search for representation, exceptions will be as important as the usual suspects.

So, here I am, attempting to wrestle something like history down into a series of key moments and milestones. Moments that have contributed to or shifted our understanding of Asian theatre in Aotearoa. So that these moments might exist as more than just memory.

❉

I. PĀKEHĀ EYES: Late 1980s to early 1990s

Helene Wong with John Clarke, Roger Hall, Dave Smith and Cathy Downe as the cast of the Victoria University of Wellington revue One in five, 1971

Collection of Rob Joiner

The history of Asian New Zealand theatre, like most ‘ethnic’ stories told in Western contexts, is often the history of having those stories told by the dominant hegemony.

While the likes of Helene Wong, one of our earliest Asian New Zealand stage queens, could be seen in many stage productions at BATS as far back the 1970s, Asian-driven narratives were still an absence yet to be filled. Wong herself has talked about how the roles she played during this time were of a colour-blind variety:

The interesting thing that happened to me back in the 70s as an actor was something that young people talk about nowadays as colour-blindness. There was a period, there was a decade when I was an actor where we seemed to be colour-blind, and I was working in theatre at the time, but I could take on roles which were not written for a Chinese character or a Chinese person.

In mainstream New Zealand theatre, the earliest account of a play written by an Asian New Zealand playwright is widely agreed to be Lynda Chanwai-Earle’s Kā-Shue (Letters Home) (1996). So what kind of Asian stories could audiences see on stage before then?

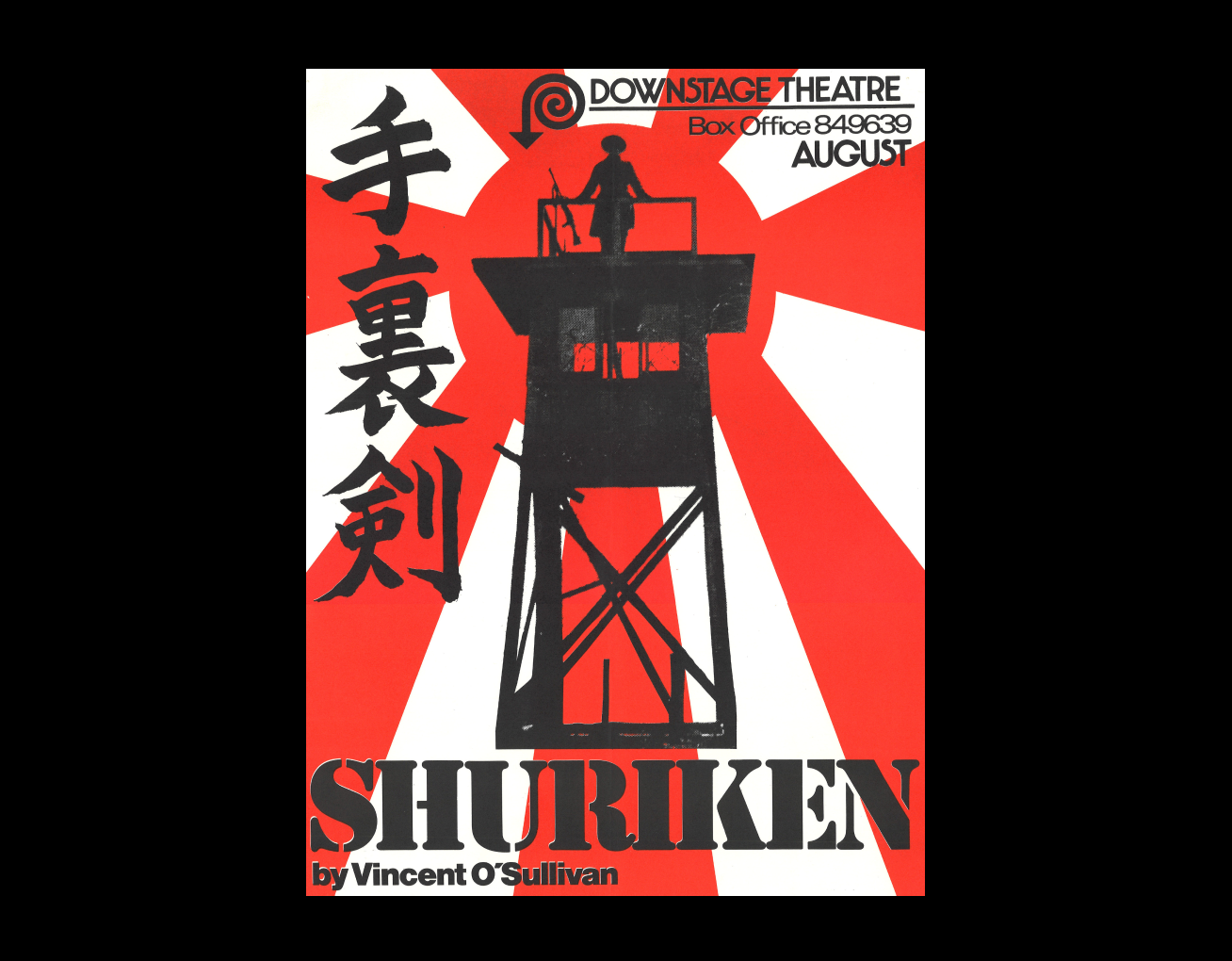

Poster for Shuriken by Vincent O'Sullivan, Downstage Theatre, 1983. Wellington City Recollect, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 NZ

Theatre academic Lisa Warrington states: ‘Prior to 1996, the primary presence of Asian voices on stage or on film was filtered through Pākehā eyes.’3 Her examples include Vincent O’Sullivan's Shuriken (1983) and Yellow Brides (1993), Stuart Hoar’s Yo Banfa (1993), which was later renamed Gung Ho, and Eileen Philipp’s Rakiura (1994).4

It’s perhaps no surprise that these portrayals of Asian characters, including Japanese war prisoners and characters in Mao Tse Tung’s China, were far cries from contemporary or modern Asian New Zealanders. These were characters from the history books in conversation with conceptions of the Pākehā imagination. Not entirely made up, but ultimately fictional interpretations of history and a people — representations that could be described as prime examples of orientalism, for lack of a better term.

Though it may be trite to say these plays were a product of their time, they inevitably reflected the cultural and socio-political landscape they were produced in; not only revealing who told the stories, but conversely who could not. The cultural roadblocks set up for Asian migrants can tell us a lot about this undefined period of orientalist theatre. At this time, immigration from Asian nations was limited by restrictive legislation. As a result, Asian communities in New Zealand were still relatively small and the first wave of Asian New Zealand theatre had to attempt to cut through invisible structures of class and racism to establish itself.

By reflecting on Asian Aotearoa theatre that wasn’t Asian-made, we can understand the history of Asian theatre in Aotearoa began as the history of stories being told about us rather than by us.

II. FLYING SOLO: 1990s

MILESTONES

Raybon Kan debuts Demeaning of Life at the New Zealand Fringe Festival (1990)

Lynda Chanwai-Earle’s Kā-Shue (Letters Home) premieres (1996)

Jacob Rajan’s Krishnan’s Dairy premieres (1997)

Lynda Chanwai-Earle as Po Po in Kā-Shue (Letters Home), TAHI Festival, 2020

Photo by Dianna Thomson

Described as the ‘first authentically New Zealand–Chinese play for mainstream audiences’, Lynda Chanwai-Earle’s Kā-Shue (Letters Home) is a semi-autobiographical dedication to her family, particularly the women in her family across three generations.

As Chanwai-Earle states in her playwright’s note, ‘Kā-Shue uncovers some of the last 150 years of a buried history in New Zealand. There has been a noticeable absence of a Chinese voice in this country.’5 The play, then, is an attempt to resist disappearance, and to unearth some of these buried histories, personal as well as historical.

Inspired by solo theatre-makers Miranda Harcourt and Jim Moriarty, Chanwai-Earle saw this form as a practical solution: ‘I would have loved to have had a full cast perform Kā-Shue but there’s such a scarcity of Asian actors so I thought I’ve got to perform all the characters and if Miranda and Jim can do it, then I can do it too.’6

The other major piece of Asian New Zealand theatre to arrive in this decade was another solo work. This time a product of Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School, Jacob Rajan’s Krishnan’s Dairy.

While Chanwai-Earle wouldn’t premiere her work until 1996, Rajan performed an early 20-minute version of his play in 1994 as part of his Toi Whakaari degree. This was later developed into the recognised, full-length version, premiering in 1997 and directed by Justin Lewis, that the New Zealand theatre industry knows so well, and launched the beginnings of Indian Ink, still one of Aotearoa’s most successful international touring companies.

Mild spoiler alert: Kā-Shue and Krishnan’s Dairy are not sentimental migrant narratives that demonstrate affability and just-like-you-ness to Pākehā audiences. Both narratives remind us that these characters, these families, do not come from some void, but rather they come from a deep well of cultural history. In Kā-Shue, this cultural history is trauma-informed and located amidst the realities of China’s Cultural Revolution, the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Sino-Japanese War and New Zealand’s poll tax policy, through the lens of immigrant Chinese women. In Krishnan’s Dairy, dreamscapes are conjured in the enactments of Shah Jahan and the building of the Taj Mahal, which counterbalance the banalities of working-class life.

Both of these works are also accepted parts of our canon — by which I mean they are widely acknowledged in publications as theatre, have been published, and have had numerous revivals. Once canonised, a theatre work in Aotearoa has a better chance of surviving the often-foggy memory of our theatre history. They live in the archives in some tangible form.

My early resistance to these narratives feels intrinsically tied to my own lack of understanding of why these narratives existed in the first place.

Jacob Rajan performing Krishnan's Dairy

Indian Ink

While I was far too young to witness the initial premieres of these works, I have had the privilege of seeing revivals of both of them since. If the idea of these early immigrant narratives can feel retrograde or outdated to contemporary (i.e., assimilated or new migrant) audiences, a sentiment my peers and myself have sometimes expressed, it’s important to acknowledge how revolutionary they were at the time. Two lone voices in a sea of silence. Chanwai-Earle has painted a clear picture of the isolated conditions of being an Asian theatre-maker at the time: ‘Kā Shue was also being written at the same time as Krishnan’s Dairy. Both Jacob and I were doing it, without even knowing each other and we were both finding our voice.’7

These works also have continued relevance, as new migrants are a growing part of our social fabric. My early resistance to these narratives feels intrinsically tied to my own lack of understanding of why these narratives existed in the first place. I didn’t want to be the fish-and-chip-shop kid,8 but that was my reality. Similarly, because these narratives existed, the pressure to tell these narratives wasn’t always thrust onto me. How lucky to have someone tell these stories so I didn’t have to.

Asian stories on stage may have exploded beyond migrant narratives, but these narratives also remain timeless.

In the end, these plays are also sighs of disappointment. They express a sense of our migrant parents’ dreams deferred. The dreams of the land of milk and honey soured. As Apu, son of Krishnan’s Dairy’s Gobi, sings at the end of the play:

Gobi Krishnan was an Indian man

His family was his kingdom

He lived for the promise

Of a better future for his children

Entho Gobi karnitcha?

Entho Gobi karnitcha?

[Gobi, what have you done?]

First trap

Of course, both plays are remembered also for being firsts of their kind. First Chinese New Zealand play. First Indian New Zealand play. The history of Asian New Zealand theatre has often been measured in firsts.9

This need and anxiety around ‘firsts’ is best articulated in filmmaker and playwright Nahyeon Lee’s debut play, aptly titled, The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom (2022) — where she writes:

Listen to me. They will use any failing and any excuse to undermine you. They will use this to pit us against each other. They will use this to deny things from each other. What — you want me to thank them for being the first? This might be my last. I want banality. I want the boring shit. I want to thank them for giving my second, my third, my tenth. So I thank them. I play nice. I say thank you, so so so much for the one opportunity that I’ve actually been busting my ass my entire life towards. Thank you.10

Maybe someday the boring shit will come easily.

The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom by Nahyeon Lee, Silo Theatre, 2022

Photo by Michael Smith

On the difficulty of theatre canons

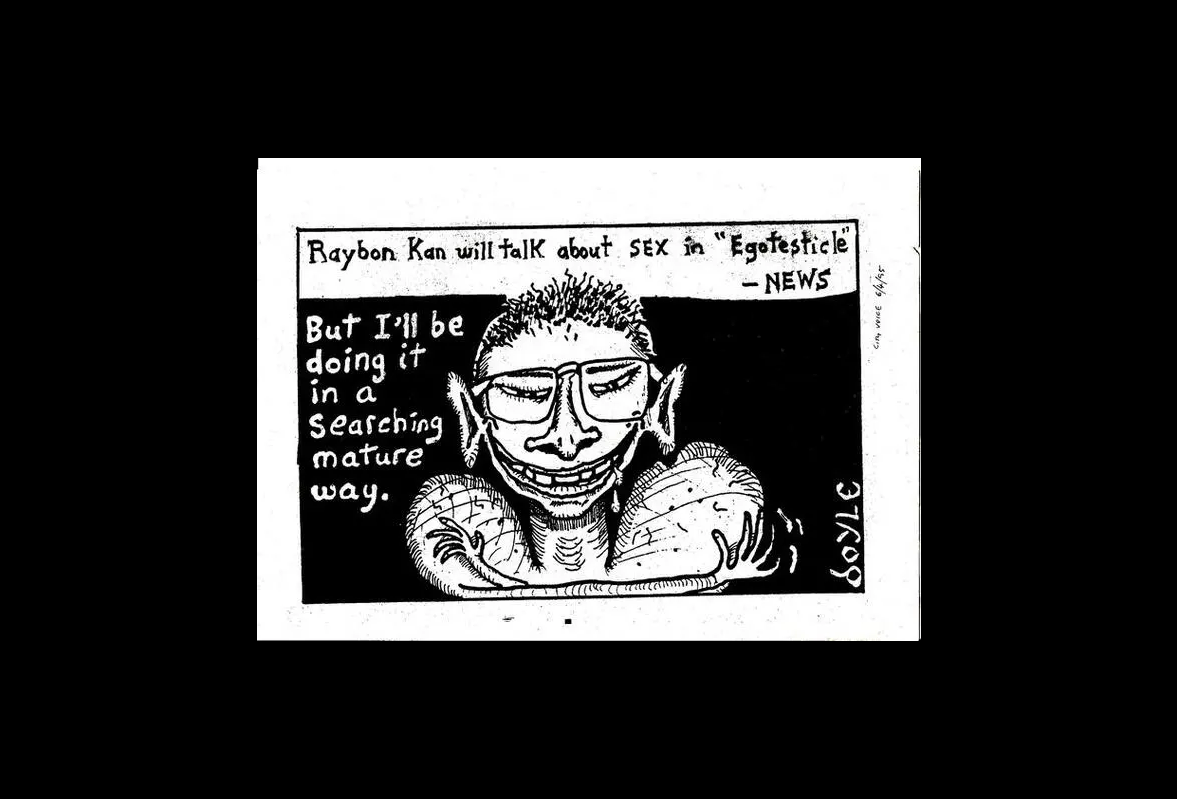

Before Asian theatre came into my life, and before any awareness of its history, Raybon Kan might have been the first Asian New Zealander I saw on stage (admittedly through a television screen).

The realisation that his presence predates our prescribed Asian New Zealand plays, as the first prominent Asian (Chinese) comedian performing shows from 1990 (Demeaning of Life at BATS for the New Zealand Fringe Festival), is no small thing. He wrote and performed several more shows at BATS throughout the decade, including Egotesticle (1995) and An Asian at My Table (1998).

I don’t mention Kan out of some desperate need to be all-inclusive, but rather a need to draw attention to the ways in which certain works are easily categorised as theatre, while others are not. This slippage is something worth wrestling with, and something I will return to. Though not explicitly calling itself theatre, stand-up comedy is a scripted and rehearsed form, occurs on a stage, and is often narrative. It’s a matter of semantics that it isn’t considered theatre. A matter of what might be considered a part of the aforementioned canon.

Martin Doyle, cartoon published 6 April, 1995, in the City Voice newspaper. Alexander Turnbull Library (DCDL-0030670)

Because there is so little written on Asian New Zealand theatre, every discussion, every publication, every review, every archive, every list, becomes an act of canon building. If a canon (often seen as a Western tendency) is largely seen as problematic or contentious, it’s because, after all, every attempt to define what is essential invariably leaves something else out. But if canons seem like an outdated methodology, they also provide a roadmap or lens through which we can view our theatre history. As a teenage cinephile, the ever-expanding and debated film canon was essential to my understanding of what movies to watch and where to begin. Without it, we might be lost.

In his 2012 essay, ‘On the difficulty of film canons’, local film critic Tim Wong writes:

Without pretending to be conclusive, a film canon should ideally perform the part of a guide to great or near-great cinema, while also opening a door to less obvious, unfairly neglected, or culturally marginalized films of significance.11

Unlike the ubiquitous nature of listing top ten films, of building film canons, a simple Google search will not yield much in the way of New Zealand theatre, especially not Asian New Zealand theatre. The only thing worse than a problematic canon, perhaps, is having barely any canon at all. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Asian theatre is something I stumbled across rather than sought out, I had no choice. It was all too hidden.

The only thing worse than a problematic canon, perhaps, is having barely any canon at all.

III. THE NEED FOR COMMUNITY: 2000s

Milestones

Lynda Chanwai-Earle’s Foh-Sarn premieres (2000)

Those Indian Guys premiere D’Arranged Marriage (2002)

Jacob Rajan receives an Arts Foundation Laureate Award (2002)

Sonia Yee premieres The Wholly Grain (2003)

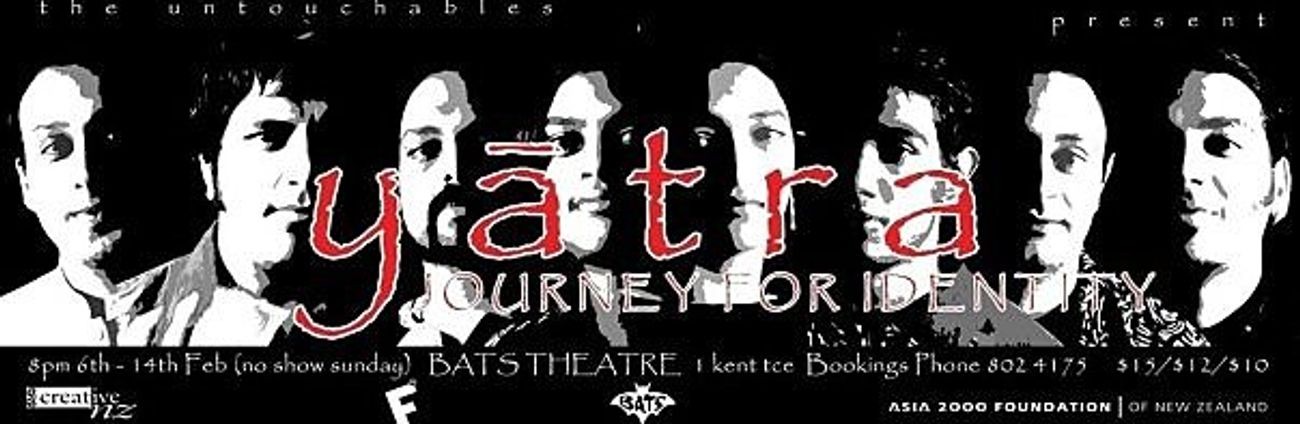

The Untouchables Collective premiere Yâtra: Journey for Identity at BATS (2004)

Prayas is formed (2005)

Oryza Foundation is formed (2008)

Renee Liang debuts her first full-length play, Lantern (2009)

Continuing Trends

Over the following decade, Rajan went on to create a stable of works within Indian Ink (The Candlestickmaker [2000], The Pickle King [2002], The Dentist’s Chair [2008]), and Chanwai-Earle did similar (Foh-Sarn [2000], Monkey [2004], Heat, [2008]). Both of them expanded beyond their solo-show roots, and sometimes drifted from recognisably Asian narratives altogether.

As both these pioneers continued making work across this next decade, so too did a new wave of Asian creatives. Following their footsteps, intentionally or otherwise, there was an ongoing development of solo shows, including D’Arranged Marriage (2002) by Those Indian Guys (which Tarun Mohanbhai and Rajeev Varma took turns performing) and The Wholly Grain (2003) by Sonia Yee.

As well as continuing the trend of solo theatre, these narratives expanded beyond the migrant stories of parents and towards the assimilation narratives of children of migrants. Both plays feature children contending with familial expectations, whether it be Sanjay Gupta in D’Arranged Marriage, ‘evading his family’s desire to see him married’, or Jocelyn Chan of The Wholly Grain, ‘who dreams about anything other than taking over the family fish-and-chip shop which, as far as her parents are concerned, is her destiny’.12

If Mohanbhai, Varma and Yee represented the independent Asian theatre sector slowly expanding, a lack of resourcing and opportunities available to Asian artists was still apparent despite these early victories and milestones. Asian theatre was still in its early days, with no discernible scene to hold or bring makers together. The programming of Asian work by professional theatre companies was still largely an anomaly.

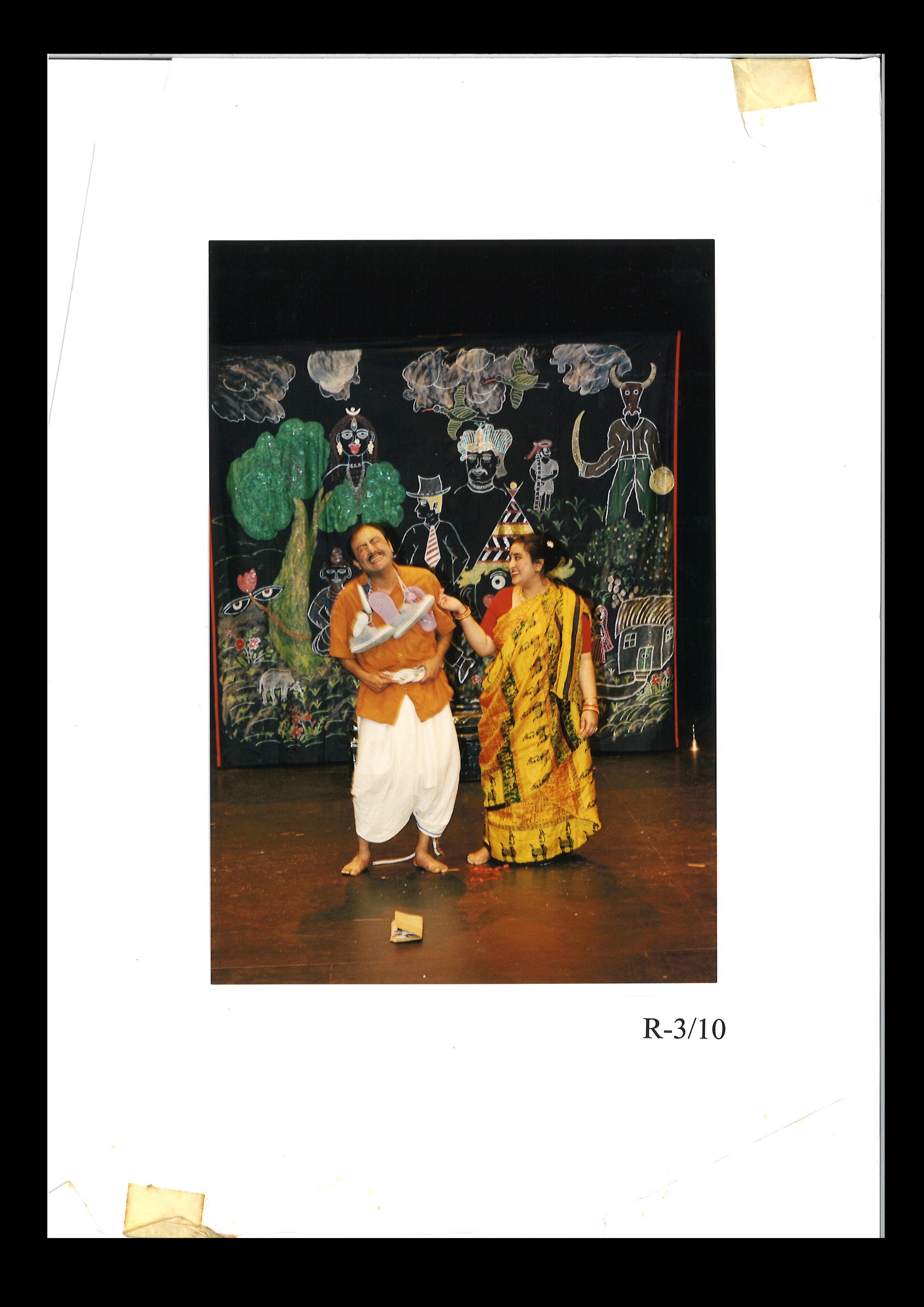

Kinu Kahar-er Thetar (Kinu’s Theatre Company) by Manoj Mitra, staged at Centennial Theatre, Auckland Grammar School, 2001

Power in numbers

Enter Prayas and the Oryza Foundation, a theatre community and an arts organisation respectively.

New Zealand’s immigration system had been transformed by the Immigration Act 1987, allowing more migrants from a wider range of Asian countries to settle in Aotearoa New Zealand. By the 2000s the increase in the country’s Asian population began to be reflected in theatre.

While Asian New Zealand theatre began in Wellington, the significance of Auckland as a major player began to emerge in 2005 with Prayas, founded by Amit Ohdedar and Sudeepta Vyas to produce contemporary Indian theatre in English for wider audiences in Aotearoa. Its beginnings were modest, premiering Habib Tanvir’s Charandas Chor: The Honest Thief (2005) at Centennial Hall at Auckland Grammar School. Today, Prayas has evolved into one of the largest South Asian community theatre and cultural groups in the country.

The Oryza Foundation, co-founded by Yee Yang ‘Square’ Lee and Alex Lee, made their debut in 2008 with Asian Tales™: Native Alienz, featuring seven short Asian New Zealand plays. The playwrights included Renee Liang and Mei-Lin Te Puea Hansen, significant writers in the Asian New Zealand theatre canon, as well as Hiroshi Nakatsuji, who is New Zealand’s best known performer of rakugo (traditional Japanese comedic storytelling) in English.

Prayas and Oryza proved to be particularly influential institutions, acting as alternative pathways for Asian theatre-makers (playwrights, actors and directors) to emerge and upskill, providing platforms and spaces for them where mainstream companies were not. If the first generation of makers felt the need to tell their own stories, this second generation saw the need for a community and ecosystem, and began to carve one out, quietly on their own terms. Sole Asian voices were succeeded by the beginnings of communities and wider networks.

Prayas helped redefine my own understanding of community theatre as an inherently pejorative thing, as lesser than ‘professional’ independent theatre. If you’re doing it without funding, isn’t that really the great equaliser?

It’s significant to consider the ways in which Prayas and Oryza nurtured the early careers and practices of those we might now call Asian arts leaders or mentors for many others in the coming decade or so (including myself). Despite their humble beginnings, both companies eventually had productions on the mainstage,13 collaborating with the likes of Auckland Theatre Company and Auckland Arts Festival.

The 2000s marked the ongoing development of the trends set in motion during the 1990s, while also planting seeds for the community to grow. The need was there, but we were still in a pivotal transitory stage. A stage marked by the persistence of some collectives, and fleeting flashes in the pan by others.

Flyer for Yātra: Journey for Identity by The Untouchables Collective, BATS Theatre, 2004

Not all collectives or companies survived this decade. Survival or sustainability wasn’t always even the end goal for some. Sometimes, as in the case of the South Asian performers forming The Untouchables Collective14 — who premiered Yātra: Journey for Identity at BATS (2004) — the desire to simply make was enough. As member and actor Rina Patel reflects:

The Untouchables Collective was short-lived, simply because we were a bunch of like-minded practitioners who wanted to come together, create and share work but we weren’t necessarily interested in formalising the group into a registered company.

They were driven by necessity rather than a deliberate vision to change the sector. Sometimes these collectives were simply about giving name to a desire for something that did not quite exist yet. And sometimes what remains are oral histories of companies and makers that once were, echoed later down the line.

Li-Ming Hu and Andy Wong in Lantern by Renee Liang, BATS Theatre, 2009

IV. A SCENE EMERGES: 2010s

Milestones

Michelle Ang performs Chop/Stick (2012)

Lynda Chanwai-Earle’s Man in a Suitcase premieres at Court Theatre (2012)

Agaram Productions is formed by Ahi Karunaharan (2012)

Proudly Asian Theatre is founded by Chye-Ling Huang and James Roque (2013)

Tawata Productions produce The Mourning After (2012) and Neang Neak’s Legacy (2013)

The Mooncake and the Kumara premieres at Auckland Arts Festival (2015)

Alice Canton premieres Orangutan (2015)

Chye-Ling Huang premieres Call of the Sparrows (2016)

Alice Canton creates WHITE/OTHER (2016) and OTHER [chinese] (2017)

Renee Liang’s opera The Bone Feeder premieres at Auckland Arts Festival (2017)

Sharu Loves Hats produces Dominion Rd the Musical (2017)

Nisha Madhan performs Fuck Rant (2018)

Saraid de Silva performs Drowning in Milk at Auckland Fringe (2018)

Ahi Karunaharan premieres Tea for Auckland Arts Festival (2018)

Chye-Ling Huang premieres Orientation (2018)

Nikita 雅涵 Tu-Bryant’s Tide Waits for No Man: Episode Grace premieres at BATS (2018)

Ankita Singh forms Oriental Maidens (2018)

Oriental Maidens premieres I Am Rachel Chu at Auckland Fringe (2019)

Natasha Lay premieres MANIAC on the Dancefloor at Basement Theatre (2019)

Gemishka Chetty and Aiwa Pooamorn perform Go Home Curry Muncha at Auckland Fringe (2019)

Ahi Karunaharan directs A Fine Balance for Auckland Theatre Company in collaboration with Prayas (2019)

Marianne Infante’s PINAY premieres at Basement Theatre (2019)

Ahi Karunaharan’s My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak premieres with Silo Theatre (2019)

The notion of an ‘Asian theatre community’ is a nebulous one, but a groundswell of new artists came into play in the 2010s, ultimately snowballing progress across the coming decade. This marked not only the growth of our stories, but an acceleration in the growth of the community surrounding the stories, audiences and makers alike.

If the decade began with individual makers continuing to work away in their own corners, chipping away slowly, countless companies began to intersect, collaborate, and change the landscape for good.

My own experiences across this decade paint it as a time of eventual enthusiasm for the growing number of Asian stories. A time when makers were still figuring out how to tell their stories. When approval and acceptance was still debated. When persistence paid off.

Asian–Māori entanglements

In Pōneke, the work of Māori-led theatre company Tawata Productions was vital in producing the early work of Ahi Karunaharan (The Mourning After, 2012) and Sarita So (Neang Neak’s Legacy, 2013) — key examples of a non-Asian company taking on the need to produce Asian work. At a time when no Wellington-based company served the specific needs of the Asian theatre community, it’s significant that someone else was able to serve that need. That those works were our first Sri Lankan and Cambodian stories on stage, often overlooked in the dominant conversations of Asian narratives, is also worth noting.

The history of Asian New Zealand theatre is the history of these overlooked partnerships.

How might remembering these stories of solidarity shape a more nuanced understanding of community?

Neang Neak’s Legacy by Sarita Keo Kossamak So, Gryphon Theatre, 2013

Tawata Productions

New kids on the block

For Tāmaki Makaurau, a wave of newcomers shifted the narrative of ‘Asian art’ in Aotearoa, running parallel with growing trends15 in Hollywood in Asian representation across the following decade.

The dynamic duo of James Roque and Chye-Ling Huang injected a dynamic energy into the sector. Both graduated in 2012 from Unitec’s School of Creative Industries acting programme, forming Proudly Asian Theatre (FKA Pretty Asian Theatre), or PAT, out of pure need to create work for themselves.

Witnessing their first production in 2013, of Chinese American playwright David Henry Hwang’s FOB, was something of a watershed moment for me. I credit it as the first time I saw Asians like myself on stage, particularly Westernised Asians in a modern and urban context. Their second show in 2014, a revival of Renee Liang’s 2009 debut play Lantern, proved even more significant — this time it was a New Zealand play. Our stories! Over the next decade were other landmark original productions, including Huang’s own plays Call of the Sparrows (2016) and Orientation (2018), as well as Marianne Infante’s PINAY (2019). At the time, it felt like no other company was consistently telling truly contemporary Asian New Zealand stories with Asian creatives at the centre.

Around the same time, Toi Whakaari acting graduate Ahi Karunaharan arrived into the Auckland scene from Wellington in 2011, first collaborating with Prayas as an actor in their show Kingdom of Cards. Where PAT often worked with smaller casts of four or five, Karunaharan developed a repertoire of sprawling ensemble plays. His body of work moved from the independent and community spaces of Basement and TAPAC to the scale of the mainstage with Silo, Auckland Arts Festival and Auckland Theatre Company. Like PAT, when he wasn’t making his own work he was advocating for others through his company Agaram Productions, which he formed in 2012.

His sweeping epic Tea (2018), a time-hopping period drama, remains a prized gem in Asian New Zealand storytelling, demonstrating scale and ambition in equal measure. Karunaharan has come to be known as a powerhouse director/playwright/actor in Aotearoa theatre.

Perhaps what made these newcomers so significant at the time was their urgent need to make work because their careers depended on it. Here were actors and storytellers driven by lack and a theatre industry that could not hold them. They became the very industry they longed for. As they did so, they contributed to the sector at large, creating ecosystems others have since thrived in.

error

Here were actors and storytellers driven by lack and a theatre industry that could not hold them. They became the very industry they longed for.

Scenes from a Yellow Peril reading at Fresh off the Page, 2018

Photo by John Rata

New play development

Playmarket’s Asian Ink programme, first launched in 2013, was the first time I dipped my toes into writing a full-length play, then titled Flesh off the Boat. It offered a one-day workshop — with non-Asian actors — the one I mentioned briefly in this essay’s introduction. While this experience deterred me from leaning into ‘Asian’ playwriting for a while, it ultimately opened the door for me to theatre, and got me into playwriting in the first place. Again, gratitude mixed with discomfort.

For Asian writers, why would you write a play if there are historically so few actors to perform it? For Asian actors, why would you train if there are no roles for you? A catch-22, a chicken and egg situation, a problem that feeds itself.

Despite a growing number of Asian actors across this decade, there didn’t seem to be enough roles for them, and a hunger for local writing grew. Proudly Asian Theatre launched Fresh off the Page in 2017 to respond to this need. While originally designed as a play-reading series for Asian actors to stay active, eventually a greater desire for new writing superseded that. Fresh off the Page became an ongoing incubator of new work. It gave emerging writers a deadline and a mentor to test their play ideas in front of an audience. More importantly, it gave writers a safe space to test stuff with their community.

Fresh off the Page, alongside other targeted playwriting and theatre development programmes, revealed the desperate need to tell our own stories. Having Asian actors was one thing, but having the roles for them was another. For sheer volume, it has become one of the most significant platforms across the whole country.16

Alongside this, through Oryza’s Asian Playwrights Lab and Agaram Productions’ First World Problems (with Oriental Maidens and Prayas), the development of new voices and new writing became one of the central goals for the community and sector.

Early drafts of two of my plays, Losing Face and Scenes from a Yellow Peril, received their first public readings through Fresh off the Page. The play-reading for the latter was an especially significant catalyst for what eventually became the Auckland Theatre Company production. I could not imagine anywhere else I might trust an organisation enough to throw up a public play-reading and see it held with the same care and enthusiasm I received. These lifelines are as significant as any award or residency. I owe a lot to the enthusiasm of the team.

It was at the first Oryza Asian Playwrights Lab (2018) that I met Ankita Singh, founder of Oriental Maidens, who later produced my show I Am Rachel Chu (2019), a response to the craze of Hollywood hit Crazy Rich Asians (2018). I credit this show with helping me embrace Asian playwriting for myself again — Asian playwriting where Asian-ness was explicit rather than an ambiguous negative space I had resisted.

No single colossal opportunity is responsible for developing my playwriting practice. No, it was a collection of many small chances, one might call them lifelines, that enabled the percolation of ideas and incremental progress towards the subsequent drafts of my plays, and opportunities to be in rooms with future collaborators. The hidden parts of the ecology, the mycelium networks, the submerged parts of the iceberg we don’t often see.

For Asian writers, why would you write a play if there are historically so few actors to perform it? For Asian actors, why would you train if there are no roles for you?

The Mooncake and the Kumara by Mei-Lin Te Puea Hansen (2017 remount)

Photo by Julie Zhu

On being tauiwi

In Tāmaki Makaurau, the content of our plays began to reflect the shifting consciousness of not just our community alone, but also our relationships with Māori, historical and ongoing. Mei Lin Te Puea Hansen’s The Mooncake and the Kumara (2015), Renee Liang’s opera The Bone Feeder and Alice Canton’s OTHER [chinese] provide key examples of Asian works that engage in dialogue between Asian as tauiwi and Māori as tangata whenua. These plays, according to Cynthia Hiu Ying Lam and Rand T Hazou, ‘express decolonial political aspirations that circumvent and challenge the hegemony of white settler coloniality by articulating reconfigured relationships between Indigenous Māori and Chinese migrants.’17

The Mooncake and the Kumara fictionalises the meeting of Mei Lin Hansen’s grandparents, a Māori woman and Chinese man. The Bone Feeder uses the events surrounding the sinking of the SS Ventnor as an act of memorial, acknowledging the relationship local iwi had in taking care of the remains of Chinese bodies.18 OTHER [chinese] isn’t a play at all, but rather a piece of documentary theatre that resists and complicates any attempt to sum up the Chinese experience. The show ends by quoting K Emma Ng:

It is easy to demand acceptance as New Zealanders from Pākehā. It is much more difficult to ask for the same from Māori. We have all seen how easy it is for the desire to belong to teeter and slip into a neocolonial agenda of ‘laying claim’ to a place. How can we belong here, become ‘from here,’ without re-enacting the violence that is historically embedded in the gesture of trying to belong?

Being tauiwi, being on Indigenous land, were things I understood in theory, but had never really questioned on a fundamental gut level. My place on this land, my place as wanting to fit in, wanting to belong, often superseded my capacity to reflect on what the cost of that belonging was.

Like our plays, our community was slowly beginning to unravel these complexities.

Funny as

As in our first decade of Asian theatre pioneers, theatre during this decade ran concurrently with milestones in stand-up comedy. Taking up space on our stages outside of the confines of plays and theatre companies, comedians were landing with a triumphant splash.

As Helene Wong reflected in 2019 for the TV series Funny As: The Story of New Zealand Comedy, ‘We’ve taken back some of the power, in the sense that we can now, [as] opposed to getting audiences to laugh at us, we’re now getting them to laugh with us.’

Asian New Zealand theatre history is littered with plays, yes, but also comedians telling their own stories, their own way. It’s a testament to our stories finding the right form to be told.

Milestones

Pax Assadi is nominated for the 2013 Billy T Award

David Correos wins the 2016 Billy T Award

Angella Dravid wins the 2017 BIlly T Award

Proudly Asian Theatre’s James Roque finds himself moving away from theatre-making towards stand-up comedy over this period too, and is nominated for a Fred Award in 2019

These outliers are, in fact, a constant, and make up a substantial part of our history.

The right kind of Asian theatre

On the edges of Asian theatre history have also been Asian makers who chose not to, or were not able to, produce ‘Asian’ work. A category I myself know well. Two of my earliest produced plays, Hippolytus Veiled (2016) and Like Sex (2016), had no Asian characters in them.

There have always been Asian makers whose work resists the widely acknowledged labels of mainstream theatre. There will always be stories we tell that are not easily boxed in. Like my own experiences writing against and towards Asian-ness, an alternative view of our canon is filled with these exceptions. If our history has often prioritised a particular brand of Asian experiences and narratives, it reveals a narrow conception of theatre, one full of poorly acknowledged outliers. These outliers are, in fact, a constant, and make up a substantial part of our history.

Hippolytus Veiled by Nathan Joe, Basement Theatre, 2015

A few years before my earliest plays, actor and writer Benjamin Teh wrote plays such as Meat (2012) and Seven Deadly Monologues (2016), exploring themes of horror and transgression.

Though perhaps best known for WHITE/OTHER (2016) and OTHER [chinese] (2017), Alice Canton’s other work sits outside of the Asian identity box, though still focussing often on documentary and social practice, with the likes of Children Talk About (2018) and Year of the Tiger (虎—hǔ). As well as improv comedy work with Heartthrobs, including MacKenzie’s Daughters (2018) or dance-theatre work like Death. Disco. Heartbeat (2019).

In Wellington, Cassandra Tse,19 artistic director of Red Scare Theatre, best known for her work as a writer of musicals and magical realism, wrote Long Ago, Long Ago (2015) and M’Lady: A Meninist Musical (2017). Similarly, Tse’s company produced plays by fellow collaborator Matt Lovaranes, including The Showgirl (2015) and MoodPorn (2019), an American-style noir and relationship drama, respectively.

A close collaborator of my own, director Jane Yonge, made notable work like Basement Tapes (2017) and WEiRdO (2017), both devised in collaboration with her performers. Her earlier collaboration with performance artist Vinay Hira, Heteroperformative (2016), a hybrid of performance art and installation, might be the closest thing to ‘Asian’ theatre she made, despite not really being theatre at all. Jane herself had leaned briefly towards, and then away, from ‘Asian’ storytelling, when she decided not to continue developing a work about the Chinese history of Haining Street. We did not cross paths until around 2020, which sparked a mutual embrace of ‘Asian’ storytelling, leading to the staging of my play Scenes from a Yellow Peril.

error

On the other end of the spectrum, is also work by companies such as iStart Chinese Theatre, founded in 2014, and Felix Creative Theatre, founded in 2015, who perform plays in Mandarin, or individuals such as Hiroshi Nakatsuji, a practitioner of traditional Japanese rakugo (translated into English). Work that sits outside our ideals of independent or professional theatre in the Western notion of canon.

How might we move past debates of too Asian or not Asian enough in our theatrical imagination?

error

Among the most influential, for me, has been the work of Nisha Madhan, who operates in the world of live art, experimental and often narrative-resistant work. While not making work about Asian-ness, she has never been afraid to centre her experiences and lens as an Indian woman as invaluable to her process.

I still remember seeing Madhan scurrying on stage, her whole body whipping around, covered in fake blood in Fuck Rant (2018); I was moved by the irreverence towards theatre. It was a far cry from her performance in Indian Ink’s 2013 Kiss the Fish (or more famously as Shanti on Shortland Street).

Nisha Madhan in Fuck Rant, 2018

Photo by Andi Crown

Madhan was a formative figure for me — because of how uncomfortably she fit into the paradigms of what I'd come to know as Asian theatre (or theatre full stop). Fuck Rant remains a delightful, ecstatic subversion of the solo show. It arguably might not be for an Asian audience, but (like all her work) it feels inextricably tied to Madhan’s lived experience as an Indian woman, and how that informs the way she lives and makes. I had seen theatre break the fourth wall before, but not like this. Not with this combination of meta-awareness, savvy and irreverence. This was the sort of deconstruction or destruction that only comes with knowing something incredibly well.

As she states in her MA-thesis-cum-manifesto-cum-website:

This is why I choose to make my own work which has turned out to be mostly experimental, live art. I did it because I needed to take matters into my own hands. Cast myself in the roles I wanted to play and create narratives that empowered me to be something other than the cute little Indian girl at the end of the Jungle Book.

An inability to see beyond the walls of our disciplines may be our ultimate downfall. One only needs to look at the way in which our theatre industry is richer for these cracks and slippages, for these unexpected collaborations.

A complaint

With the rise of our voices on stage (and on screen), driven predominantly by the independent sector, a newfound confidence in voicing dissent and dissatisfaction at a broken system became palpable. Social media, too, became a vehicle for communities critiquing organisations or rallying together.

It wasn’t uncommon for communities to feel alienated from the likes of major companies, particularly Auckland Theatre Company’s mishandling of some orientalist tropes and cultural appropriations over the years. The Woman Who Spoke Japanese in Her Sleep (2009) and The Good Soul of Szechuan (2014) are some more recent examples of our stories told through ‘Pākehā eyes’ on our mainstages.

I remember Auckland Theatre Company’s play-reading for UK playwright Howard Brenton’s The Arrest of Ai Wei Wei (2015) being an example of something we felt particularly affronted by, where non-Asians were cast in Asian roles, and a few of us from the community sat in on the reading in protest after rallying together on social media.

It seemed as if we were neither cast in roles designed for us, nor in roles that could be open to anyone.

Promotional image for The Good Soul of Szechuan, featuring Robyn Malcolm in the roles of Shen Teh and Shui Ta, 2014. Reviewer James Wenley wrote: "multi-ethnic casting only goes some way to answering the uncomfortable orientalism".

Auckland Theatre Company

Perhaps the last major example of complaint as protest would come at the end of the decade with Chye-Ling Huang’s infamous Facebook post, bemoaning the lack of diversity in a production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (2019):

I cannot begin to express my absolute rage that this is still a conversation [that] needs to be had, and something I feel the need to make a statement about on a public platform. What else is there to do? Surely ATC knows the role it plays, how influential it is, how much resource and responsibility [it] has as the largest and most well funded theatre company in Auckland. … It’s beyond frustrating to see an easy opportunity to be inclusive go to absolute waste. What can be done? We are not their target audience, and if the monetary value on diversity doesn’t stack up, why change?

The gauntlet had been thrown. If you wanted to tell our stories, you would do it with us, not without us. It’s easy to take this attitude for granted, but, at the time, it felt like tectonic shifts were happening in the industry.

A confidence in telling our own stories meant feeling able to hold institutions accountable. We knew our stories had value, but everyone else was catching up. The beginning of the next decade saw the culmination and consequences of these complaints, with more Asian-led stories as well as colour-blind casting. The freedom to represent your community and beyond. No longer having to choose between the aspiration of being a neutral body or to only being tokenised.

A confidence in telling our own stories meant feeling able to hold institutions accountable. We knew our stories had value, but everyone else was catching up.

Behind the scenes of the trailer for BASMATI BITCH by Ankita Singh, Auckland Theatre Company, 2023

Photo by Ankita Singh

V. THE PRESENT DECADE (2020s—)

Milestones

Asian-led radio plays have a brief moment during lockdown (2020)20

Ahi Karunaharan is awarded an Arts Laureate (2020)

Asian Waves is formed in Ōtautahi (2021)

Ahi Karunaharan’s The Mourning After is remounted (2021)

Sherry Zhang and Nuanzhi Zheng’s Yang/Young/杨 premieres as part of Auckland Theatre Company’s Here and Now programme (2021)

Talia Pua premieres Pork and Poll Taxes (2021)

Aman Bajaj and Bala Murali Shingade’s Boom Shankar premieres at the NZ International Comedy Festival (2021)

Shriya Bhagwat premieres The Kamasutra Chronicles at Basement Theatre (2022)

Fresh off the Page goes national (2022)

Krishnan’s Dairy is remounted and has its 25-year anniversary (2022)

Scenes from a Yellow Peril premieres at Auckland Theatre Company (2022)

Foundation North’s Asian Artists’ Fund is launched (2022)

Nahyeon Lee’s The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom premieres with Silo Theatre (2022)

Sam Wang’s Skyduck: A Chinese Spy Comedy plays at Auckland Arts Festival (2023)

Ankita Singh’s BASMATI BITCH premieres with Auckland Theatre Company (2023)

Nahyeon Lee starts Punctum Productions (2023)

Proudly Asian Theatre celebrates its ten-year anniversary and takes a break (2024)

A Slightly Isolated Dog premieres Our Own Little Mess at Aotearoa New Zealand Festival of the Arts (2024)

Julia Croft and Nisha Madhan premiere Thelma and Louise at the Civic (2024)

Punctum Productions premieres A Short History of Asian New Zealand Theatre at Basement Theatre (2024)

Proudly Asian Theatre receives funding from the Creative New Zealand Arts Organisations and Groups Fund (2024)

Jungwhi Jo is cast as Tinkerbell in Auckland Theatre Company’s Peter Pan (2024)

Asian New Zealand theatre capital

Perhaps it’s very typical that a mainstage New Zealand theatre company chose to programme a Chinese Australian play as their first Chinese New Zealand play. Programmed by Auckland Theatre Company, Michelle Law’s Single Asian Female, directed by Cassandra Tse, landed in 2021 to enthusiastic audiences. Though an Australian play, it had been localised to at least appear like a Kiwi story, relocating the setting from Australia’s Sunshine Coast to New Zealand’s Mount Maunganui.

Here we had the biggest theatre company in Tāmaki Makaurau commit to a contemporary Chinese play with Chinese leads (Kat Tsz Hung, Xana Tang, Bridget Wong). More notable than the programming of it was the reception. Audiences were hungry for it. It caught the attention of the mainstream audience like no other Chinese play had.

While ‘hardly ground-breaking’, as Renee Liang reminds us, it recalled narrative tendencies and trends of earlier Asian New Zealand works (Kā-Shue, Lantern). But we had finally made it to the ASB Waterfront Theatre, playing to a wider audience and a new generation of theatre-goers. The success of Single Asian Female proved a valuable signpost for the flood of Asian programming to come. The year that followed was suitably abundant in Asian theatre.

Auckland Theatre Company presented their first actual Asian New Zealand (and Queer) play with Yang/Young/杨 by Sherry Zhang and Nuanzhi Zheng, as part of Here and Now, their youth company programme. Emerging company Hand Pulled Collective also introduced first-time writer/director Talia Pua’s debut Pork and Poll Taxes, supported by Proudly Asian Theatre. New playwrights Aman Bajaj and Bala Murali Shingade’s co-written bromantic comedy Boom Shankar was also an indie hit, debuting at the New Zealand International Comedy Festival.

Yang/Young/杨 by Sherry Zhang and Nuanzhi Zheng, Auckland Theatre Company, 2021

Then came 2022, with my own play, Scenes from a Yellow Peril, directed by Jane Yonge, and co-produced by Sums Selvarajan (SquareSums&Co) and Ankita Singh (Oriental Maidens), for Auckland Theatre Company. Looking back, it’s easy to see Scenes as an act of reclamation on my part, a disavowal or acknowledgement of a younger playwright’s internalised racism. An eventual sense of the themes of my life finally catching up to me. But also, finally being given permission to write myself into existence. When I was cast into the trope of the ‘yellow peril’ (however sympathetic) as a high school teenager in 2009, I had no idea I would take 13 years to reclaim and subvert that. Writing as an attempt to avenge my younger self.

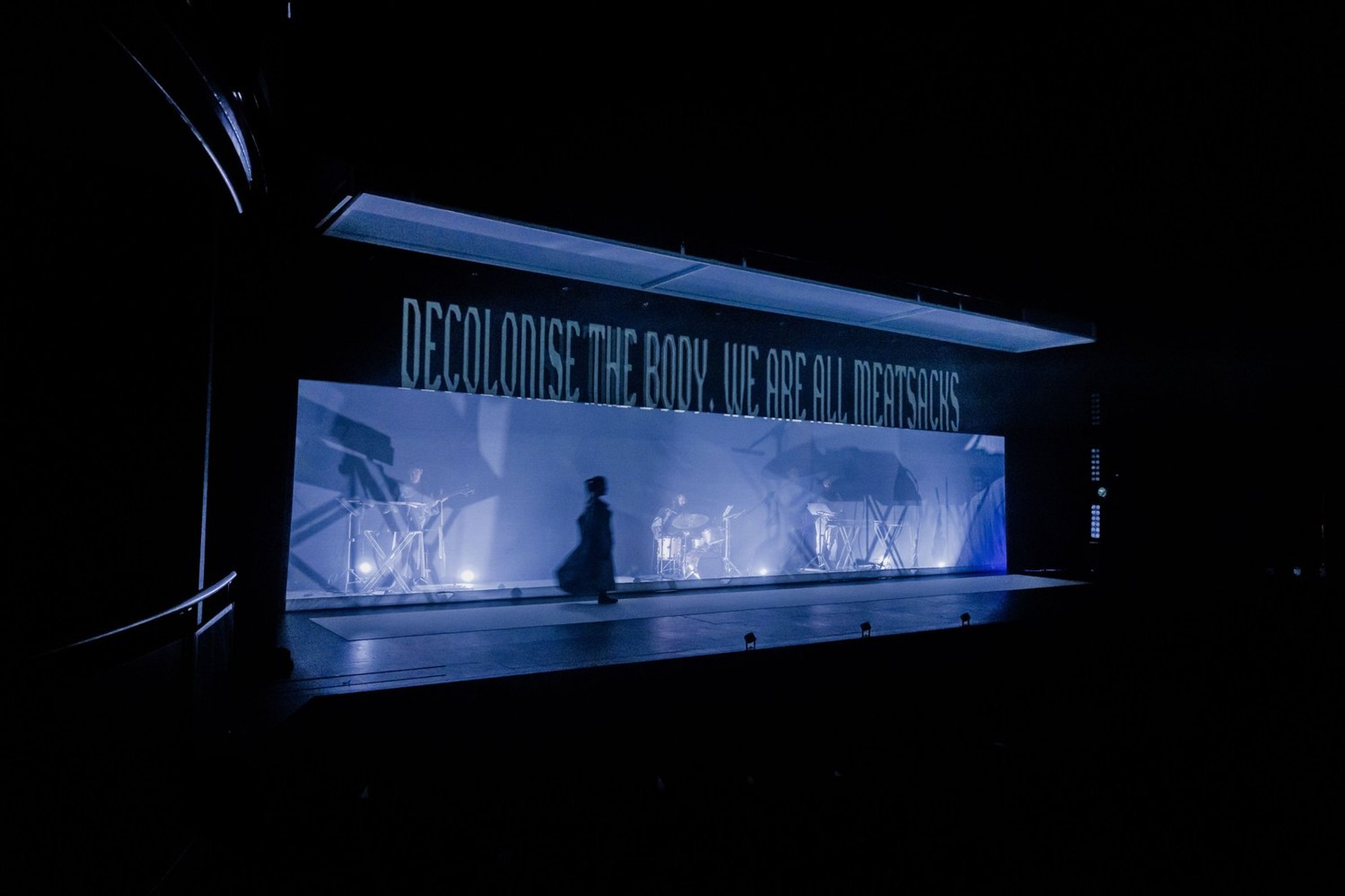

Exemplified by Nahyeon Lee’s The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom with Silo Theatre, mainstage Asian plays in Auckland focused on meta-theatrical examinations of race, unafraid of engaging in capital I identity politics. Commenting on stereotypes we had grown up internalising, rather than recreating them at face value.

When I was cast into the trope of the ‘yellow peril’ as a teenager, I had no idea I would take 13 years to reclaim and subvert that.

In 2023 genre was king, taking centre stage with plays such as Louise Jiang’s Actor//Android (sci-fi), Sam Wang’s Skyduck (spy-comedy) and Ankita Singh’s BASMATI BITCH (dystopic, martial arts-dramedy); and Aman Bajaj and Bala Murali Shingade’s Boom Shankar (action-fantasy-comedy) had a return season as part of Q Theatre’s MATCHBOX programme.

Proudly Asian Theatre presented two new play-writing debuts with Hweiling Ow’s Not Woman Enough and Jill Kwan’s How to Throw a Chinese Funeral. Nahyeon Lee launched Punctum Productions, presenting the redevelopment of my first play, Losing Face (FKA Flesh off the Boat),and Nuanzhi Zheng’s second play, Chick Habit.

Bala Murali Shingade and Aman Bajaj in the Boom Shankar programme, Q Matchbox, 2023

Q Theatre

If 2024 has turned out to be lacking any Asian New Zealand works from any of our mainstage theatre companies, perhaps it is a necessary reminder that progress is never linear. Auckland Theatre Company’s production of Ahi Karunaharan’s a mixtape for maladies originally scheduled for this year has been postponed until next year.

Proudly Asian Theatre also took a programming hiatus this year, as well as running a Boosted fundraising campaign, after ‘staying afloat for ten years with no operational or administrative financial support and limited business knowledge on a shoestring.’

But where scripted plays have been absent, movement-based performances stood strong, including Yin-Chi Lee’s immersive dance work This Room is an Island (first developed in 2022), presented at Te Pou Theatre, Cindy Jang Barlow’s I Don’t Wanna Dance Alone (first developed in 2023) at the Auckland Arts Festival, and Artham Dance Company’s Yāṉum at TAPAC.

And there’s been work permeating with Asian-ness in unexpected ways, in content as well as through collaboration: in Natano Keni and Sarita So’s O le Pepelo, le Gaoi, ma le Pala‘ai | The Liar, the Thief, and the Coward; in Jane Yonge and Leo Gene Peters’ Our Own Little Mess; and Nisha Madhan and Julia Croft’s Thelma and Lousie Don’t Die.

Scenes from a Yellow Peril by Nathan Joe, Auckland Theatre Company, 2022

Photo by Andi Crown

Elsewhere in Aotearoa

If the rise in Asian theatre has felt astronomical in Tāmaki Makaurau, Pōneke and the rest of Aotearoa were quieter in this regard.

But why?

It might be a simple matter of numbers. A total of 307,230 people who identify as Asian lived in Tāmaki Makaurau, the largest city in Aotearoa, in 2013; a number that increased to 442,674 in 2018 and now stands at 518,178. Compare this to the Pōneke population of 79,314 people identifying as Asian. Perhaps it’s no wonder, then, that the capital found itself lagging behind.21

Add to that, Tāmaki Makaurau has had a history of targeted funding, including Creative New Zealand and Foundation North’s Auckland Diversity Project Fund (offered between 2015 and 2019), for attendance and participation in the arts by Māori, Pacific and Asian audiences, and, more recently, the Asian Artists’ Fund (now in its third year), which independent Asian theatre projects have been massively supported by.

error

The future across the motu is promising, though …

Asian Waves (FKA Yugto Productions), a new Asian theatre collective based in Ōtautahi, might be the first of its kind in the South Island, launched in 2021.

Fresh off the Page spread its wings in 2022, and is now a national programme, covering Ōtautahi and Pōneke, as well as Tāmaki Makaurau.

Kia Mau presented O le Pepelo, le Gaoi, ma le Pala‘ai, co-written by Sarita So and Natano Keni (I Ken So Productions), and Nadia Freeman’s The Girmit, in the 2023 festival.

New writers such as Kiya Basabas and Cadence Chung are working independently in Pōneke.

Patty Klinpibul premiered Patty with a WhY in Ōtepoti earlier this year.

Cassandra Tse’s latest play, Before We Slip Beneath the Sea, presented by Red Scare Theatre Company, Pōneke, is due for presentation later this year.

... in an attempt to process all these competing histories, I turned parts of the essay into a show.

A short history

When I was first asked to write this essay, I enthusiastically said yes. I felt honoured to be asked, not realising the complexity and density of this history, not realising how complicated my own entanglement with it is. Like most theatre-makers, I prefer the act of making work for live performance rather than to be read. So, in an attempt to process all these competing histories, I turned parts of the essay into a show. The result was A Short History of Asian New Zealand Theatre, a performance essay crossed with a spin class, where a different performer rode a bike while delivering a lecture every night. It seemed the best way to share theatre history was through theatre itself. The best way to work it out was to work it out together, sweating and sharing.

A Short History of Asian New Zealand Theatre by Nathan Joe, Basement Theatre, 2024

Photo by Jinki Cambronero

The show feels comparatively concise (a short history, after all) next to this essay. This essay has had a tendency to swell and bloat the longer I spend with it, the more histories I uncover, the more definitive I want to be. To include all the names the show couldn’t. To celebrate the artists who may not always feel a part of the Asian theatre community. To acknowledge the artists who never had community to fall back on.

He aha te mea nui o te ao? He tāngata, he tāngata, he tāngata.

What is the most important thing in the world? It is people, it is people, it is people.

Despite the loneliness and hurdles our earliest Asian theatre-makers may have faced, the accumulation of growth, all this incremental change, has been worth it. History has been made. No — we are constantly in the midst of making it.

So, as representation is further and further achieved … where to next?

A Short History of Asian New Zealand Theatre by Nathan Joe, Basement Theatre, 2024

Photo by Saraid de Silva

VI. FIELD NOTES FOR THE FUTURE

‘A dark bewitched commitment to the lure of Progress (and its polar opposite) lashes us to endless infernal alternatives as if we had no other ways to reworld, reimagine, relive, and reconnect with each other in multispecies wellbeing.’

— Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

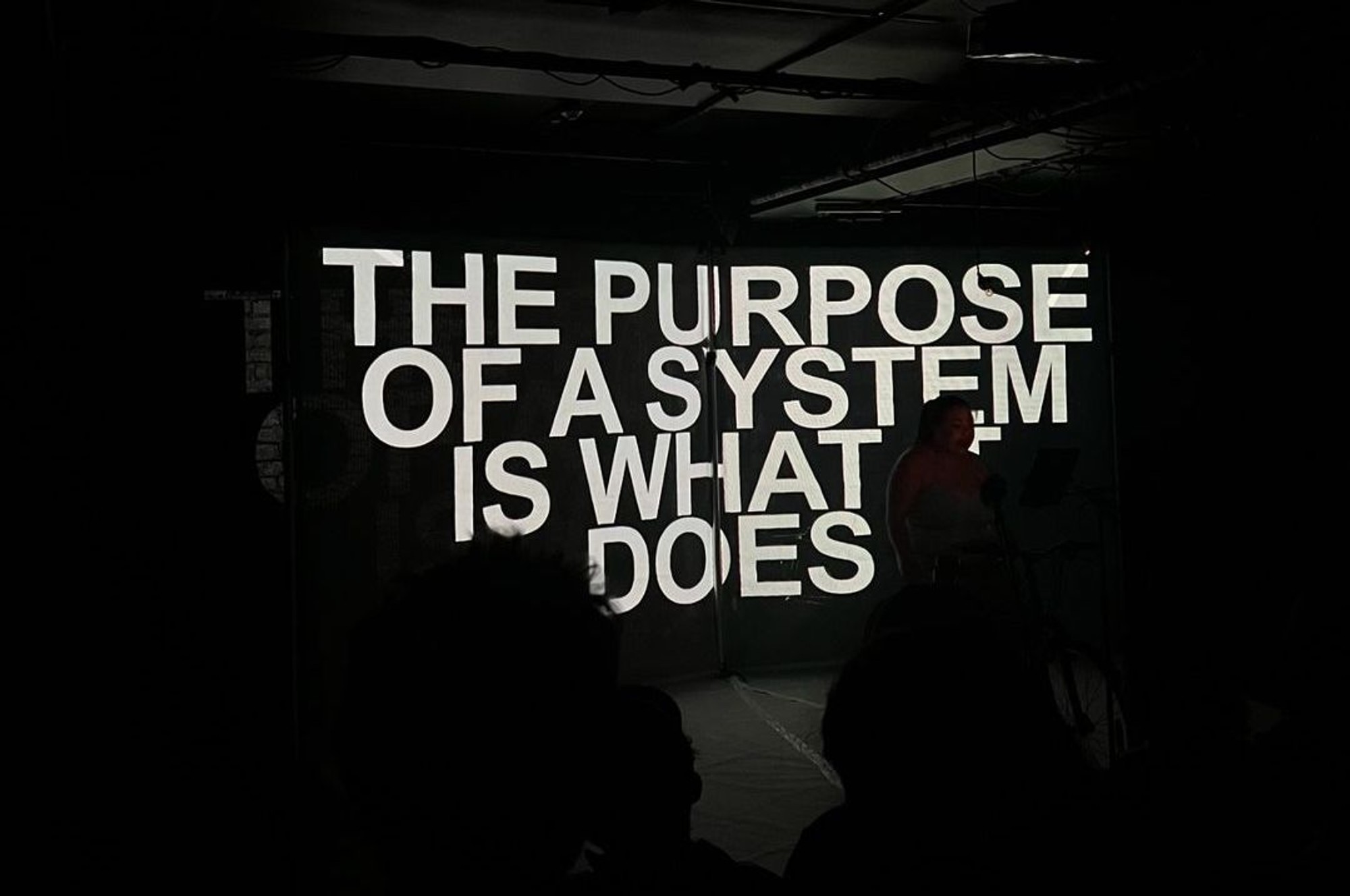

If the purpose of a system is what it does, then Asian New Zealand theatre has done a remarkably good job of better and better representing us over the last 30 years. It has brought more and more of our community onto the stage, as well as into the seats of the audience.

It has also bought us a seat at the table.

But this table is a dirty and rickety old thing. Its foundations are mighty weak, and demands for more representation are certainly not the answer.

Representation is a bottomless well that cannot be filled. Representation should not be taken for granted, but representation is also the bare minimum.

Reflecting on my short time as creative director at Auckland Pride, I was often tasked with similar questions of representation in our arts. Like the Asian community, the Queer community is also an elastic, ever-growing group with smaller sub-groups. As in the Asian community, it is easy to mistake the success of one part of the Queer community for the whole. It is similarly easy to build a notion of what Queer or Asian work should or must look like to be accepted, at the exclusion of others.

In the Auckland Pride office, we often talked around ideas of Queer futurity (thanks Julia Croft and Hāmiora Bailey). Or what José Esteban Muñoz describes as an ideality: ‘Put another way, we are not yet queer. We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future.’22 A reminder that we must look backwards to look forward. It all comes back to whakapapa.

After all, what is the point in all this progress, all this representation, if we take the past for granted? How can we know what progress we’re even making if we have nothing to measure ourselves against?

Liberation, unlike representation, is difficult to quantify, though. It is not measurable through the number of productions on stage per year or the amount of funding allocated to Asian artists. So, where might liberation lie?

Perhaps somewhere in our relationship with each other.

In asking whether ‘Asian’ is a useful term.

In asking whether ‘theatre’ is a useful term.

In more nuanced conversations around what we want the function of art to be in Aotearoa.

In expanding the limitations and borders of our community.

In revivals of our Asian New Zealand classics so we might share them with new generations.

In building a canon so we might know what those Asian New Zealand classics are.

In building multiple canons and multiple histories, so our perspectives are many.23

In constantly challenging what Asian New Zealand theatre should look like.

In remembering that the business of the theatre industry is not the same as a theatre community.

In the invitation to those who have been left out of conversations of Asian New Zealand theatre.

In remembering that the master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house.

In remembering representation is a stepping stone rather than the end goal.

Then maybe, just maybe, the search for representation will become a thing of the past.