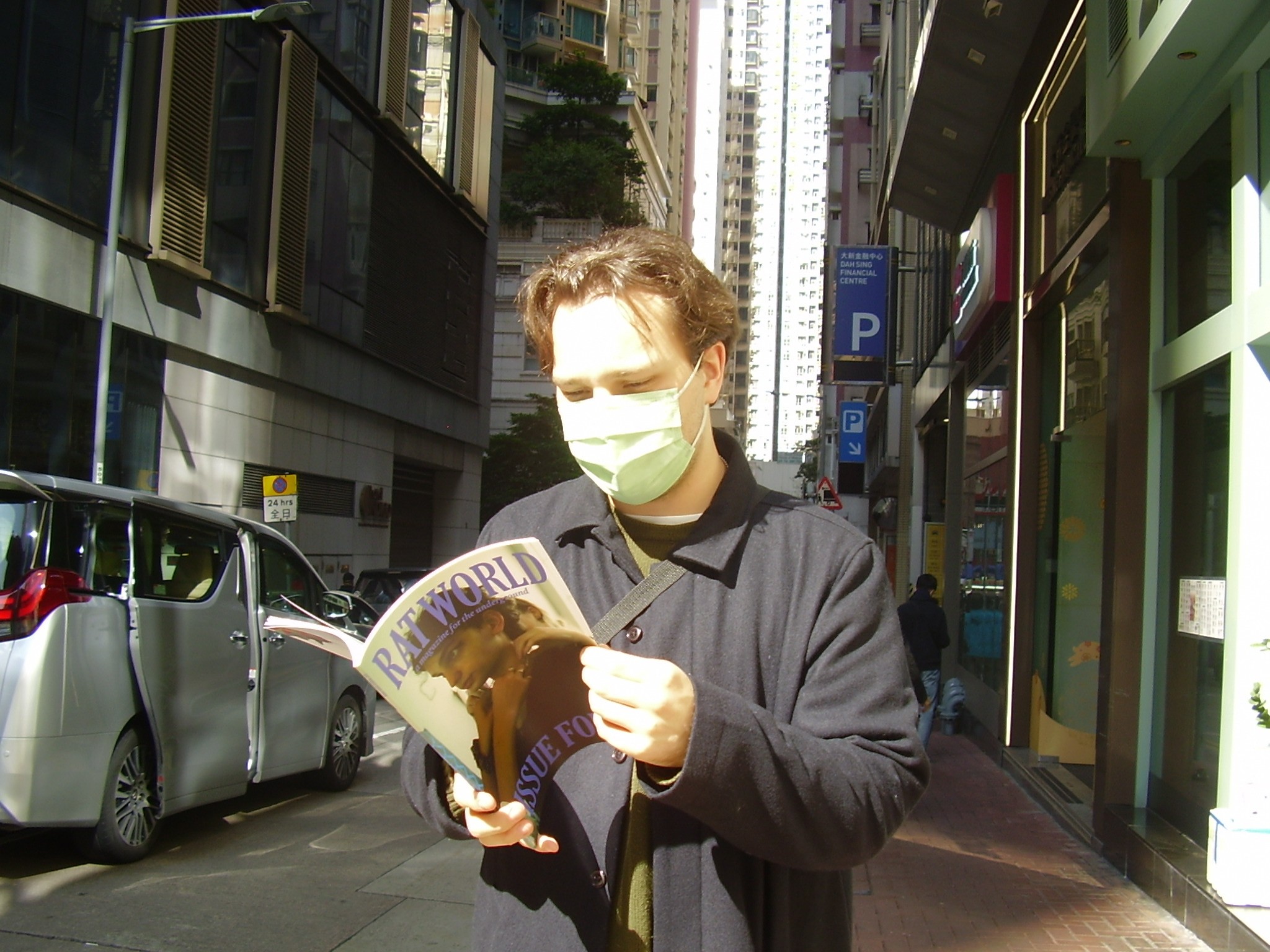

Jennifer Cheuk shares the story behind Rat World magazine — making the case for print in the age of algorithms — while tackling the ever-elusive question: ‘What’s your practice?’

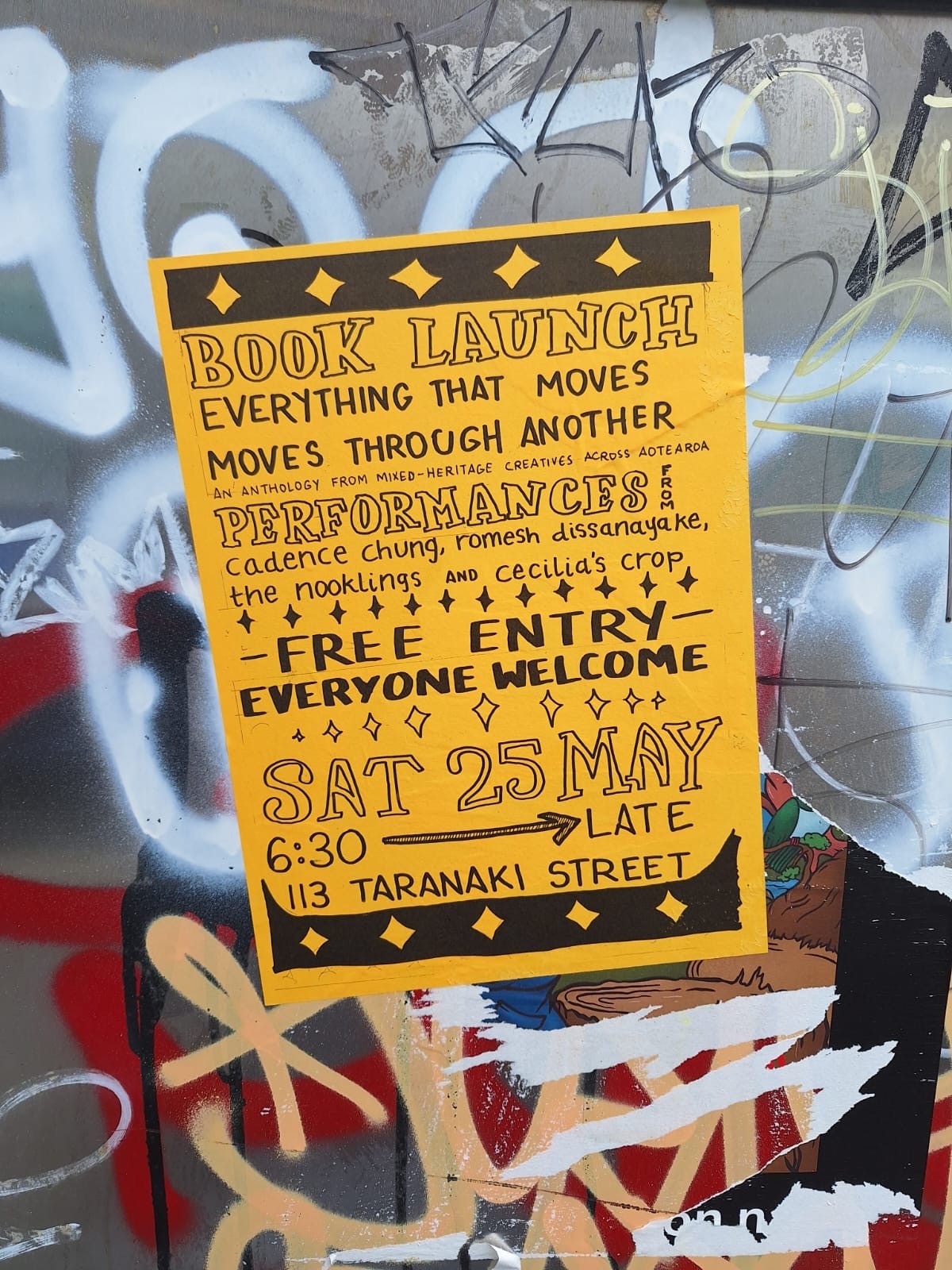

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another book launch poster, 2024

I don’t know what ‘practice’ means

People have been asking what my ‘practice’ is for a while now, and I never know how to answer. Part of it might be because I don’t know what the word means. So I thought now would be a good time to Google ‘what is arts practice?’. Unfortunately, the definition didn’t make it any clearer for me. How do I approach my work? I haven’t thought about it before. My practice is just doing. Can I say that?

Perhaps you can tell that I did not study fine arts. I always worried that this would hold me back, and I used to regret not taking up my offer at Elam. But I realise now that my creative work was born out of this very specific freedom; without the constraints of critical theory and academia, my idea of ‘practice’ was no different from that of brushing my teeth.

I enjoy art as an experience, rather than an intellectual pursuit. My dad grew up in slums, and yet he still showed me van Gogh. My mum grew up in rural Aotearoa and yet she still sat down with me to watch slow-moving independent films. Their worlds were about survival, so much more than I could ever fathom, and still they saw art as symbiotic with their existence. Art was real and it existed alongside a reality of suffering and survival. We enjoyed the stillness of art as its own thing; art was a thing in the real world to be observed by real people. And in no way am I denigrating the necessity of critical arts conversations; I just find it interesting that this is the way I was introduced to art — not as a philosophical debate, but simply as something people did.

This idea of realness, and of just doing, presents itself a lot in my approach to Rat World.

Rat World: A brief history

Rat World is an independent print magazine and collective that I started in 2022 with Aidan Dayvyd, the graphic designer. I say it began on a whim, but as I track the events that led to Issue One, I’m not so sure anymore.

I had been trying to get into the arts scene since I started university in 2017, and started out as a theatre reviewer for the youth arts magazine Tearaway. This meant that I was invited to some very fancy opening-night events, but I was a bit of an invisible presence. As I started to attend more of these openings, I couldn’t understand why they made me feel so inferior and uncomfortable. Why couldn’t I talk to these people properly? How did my friends at the time always seem to be advancing in the industry? What was wrong with me? I wasn’t interested in the right things, I was talking too much or too little and I never knew the right people. Making connections seemed to be the only way upwards and I wasn’t invited to the right parties to start the process.

I felt like a print magazine made by two nobodies was the best way to directly confront the publishing establishment.

Rat World Issue Three, 2023

In January 2022 I was sick of feeling like this, so I floated the idea of starting Something to showcase all the cool stuff that was going unseen. This Something very quickly became a print magazine, for five reasons:

- A magazine can showcase a broad range of forms and styles — from comics to essays to photography. It’s essentially a collection of cool stuff.

- A print publication validates the work of emerging creatives. To hold your poem in person, to feel the ink of your work on the glossy pages, is an active experience. Your work exists.

- Although it’s a lot better now, I felt like a print magazine made by two nobodies was the best way to directly confront the publishing establishment. We were challenging them in their own medium. As Ash Davida Jane and Stacey Teague from Tender Press say: ‘there’s still a lot of privilege at play in who gets published — or even in who has time to write a book’.1 I wanted a space for people who were just starting, who didn’t know where to get started, who had never been able to start.

- Physical publications take up space. In response to his debut exhibition at New York’s Gagosian Gallery, curator Antwaun Sargent talks about ‘spatial empowerment’ — taking up space through art. And with a commitment to marginalised voices first and foremost, I felt drawn to this concept of making space in the real world.

- I loved the way that communities seemed to grow around zine-making and independent publishing; this form is built on people and connection. Zine and indie print history is subversive, anarchist, political; it is riot grrrl, it is Black activism, it is comix — and I wanted to pay homage to the phenomenally punk history of independent magazines.

In retrospect, Issue One would have been a lot easier if I only published my friends, but this was not what Rat World was meant to be.

Rat World Issue Three launch party poster, 2022

Shortly after figuring out that this was to be a magazine, the name ‘Rat World’2 came about quite quickly.

Rat World was met with a lot of interest from my friends. In retrospect, Issue One would have been a lot easier if I only published my friends, but this was not what Rat World was meant to be. I was adamant from the very beginning that this Something would not be just for my friends. I had experienced enough rejection with the subtle implication being: ‘We don’t know you.’ So instead, I cold-called a bunch of artists whose work I liked and felt I hadn’t seen enough traction around. Rat World Issue One was made possible by the writers and artists and musicians who saw something in this idea, and who trusted me to pull it off in two months.

We launched in March 2022 at NiceGoblins — a tattoo parlour on Dominion Road. What I remember most about this launch was the fact that not everyone knew each other. And yet there was always a buzz of conversation. Afterwards, I received messages thanking me for bringing everyone together. But it wasn’t me, it was the publication. Rat World brought everyone together in the same way communal zine tables bring everyone together. Seven issues later, and we still do a launch party for every release. I still make sure to choose an impossibly small, off-the-cuff venue3 in the hope that some new creative collaboration or artistic connection might begin that night. Our launch parties have often been described as ‘house parties’ and I feel a sense of pride at this. It’s difficult to show up to a wine-and-cheese bookstore launch when you don’t know what wine to ask for. But house parties — people float in and out with comfort and ease, listening to music, striking up conversations with strangers, spilling drinks and laughing.

Rat World brought everyone together in the same way communal zine tables bring everyone together.

Rat World workshop at Late Night Art in the City, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2022

Anti-Algorithm

On the flipside, we also received a flurry of questions right after Issue One was released and I quickly began to notice a pattern: ‘Who is this for?’ or ‘Why is it so broad?’ were the most common. When I started Rat World, there was never a doubt in my mind that this publication would feature everything from music to animation to flash fiction to photography. This was a magazine for creative work that I found interesting; that I didn’t find interesting; that you found interesting; that you didn’t find interesting.

There is no recommendation algorithm in Rat World magazine.

Rat World library at Late Night Art in the City, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2022

The growing influence of algorithms in social media has deeply affected the way I think about creative ‘practice’ and the shifting realities of independent publishing. In her 2020 essay ‘Embracing freaky futures’, Gabi Lardies fears that the digital landscape has condensed the breadth of work we consume: ‘I get freaked out that everyone I know consumes the same content along with everyone I don’t know’. Four years later, this comment rings both true and not true at once. While we still see the compression of content into algorithmically pushed trends and styles, this sameness is interrupted by the fact that social media algorithms can often warp the online world into a unique reality for each user. There is no guarantee that we see the same content, even if we search the same question. And both of these things shield us from finding truly new art, culture and conversation. Algorithms curate an online experience tailored to our very particular interests at a single point in time, and in turn, our interests mirror the algorithmic curation. This reached its peak during Covid lockdowns. Now, a sort of human–machine mise en abyme occurs in our social media platforms, divorcing us from experimentation, shielding us from ever needing to confront the fact that we’ve had the same interests we have had for the last ten years. As Kyle Chayka, The New Yorker staff writer and author of Filterworld: How algorithms flattened culture, says: ‘we need to not just consume things that are algorithmically recommended, and we need to maybe bring back a little bit of the human curation and tastemaking that we’ve lost in this total dominance of algorithmic feeds’.

Rat World Issue Three, 2022

Close your eyes for a moment and imagine yourself in a library. Walk around and admire the different clothed spines of each book. You want to find something in the Fantasy section, but that’s at the back corner of the building. So you have to walk past History and Romance and Science Fiction to get to the section you want. In this process, something in Romance catches your eye … you pause and pick up the book. You don’t usually like that sort of stuff, but it seems interesting. You hold on to it while you continue on your way to the Fantasy section.

Digital platforms teleport us directly to the section we want, so we miss out on ever seeing what may be of interest somewhere else. There is no journey — no flicking through pages, no looking through contents — to get there.

Aidan Dayvyd with Rat World Issue Four, 2023

Social media algorithms have stifled creative experimentation through the thinly veiled concept of digital marketing.

Breadth of art, experience and style is one of the most crucial ways to fight this algorithmic flattening of creativity. In 2023 I did a talk at the inaugural Small Press Fest in Dunedin called ‘Anti-niche: Rats against algorithms’. This discussion explored the anti-algorithmic capabilities of magazines and anthologies, presenting a new (or rather old) way to engage with information. Social media algorithms have stifled creative experimentation through the thinly veiled concept of digital marketing. Chayka comments: ‘you have to get engagement to succeed in the algorithmic feed. You need to please 100 people, then 1,000 people, then 100,000 people, and that iterative process doesn’t work for all forms of culture’. If you’re an illustrator, once the algorithm learns the style of work you post, it’s very difficult to convince it that you would like to try a different colour scheme, or pen type, or editing style. How do you break out of this arbitrary niche that you have fallen into? How do you play when you can quantifiably see your ‘likes’ decrease with each new experiment? Relearn what it means to do whatever you want, whenever you want. Rat World platforms a range of different works because the world is not an algorithm. We should not be bombarded only with things we are predicted to like — we should be challenged to like films and literature and food and fashion that are unfamiliar to us.

In every universe, I would have chosen the format of a print magazine for Rat World.

Jennifer Cheuk and Achille Segard at Rebel Press, Pōneke, 2024

Rat World collaborative poster at Late Night Art in the City, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2022

Collective practice (I still don’t really know what ‘practice’ means)

Rat World confronts individual interests and biases not only in its breadth of content, but also in its editorial process. I am aware of my personal tastes and cultural biases that come with being me — a mixed Hong Kong Chinese person, a first-generation university student, a lover of spaghetti — and I challenge these actively in each issue. I talk with people at our launches, at zinefests, at arts events, about what they feel is missing from the arts landscape, what they wish they could see in magazines. I collaborate often with other organisations or artists to showcase work that should be platformed — not because I am personally invested in it, but simply because the work is being created. I sometimes worry that Rat World doesn’t have a particular style, but it does: It’s a style created by us together.

Abel Mercer observes the common want of artists — from Amy Winehouse to Virginia Woolf — to just make the work they want to make, and quotes Winehouse: ‘Success to me is having the freedom to work with whoever I want to work with, to always be able to just fuck everything off and go to the studio’.4 Rat World is not just about platforming emerging and under-represented creative work, it’s also about forging a way of collaborating with artists that gives them power and presence in the publication. The ‘fuck everything off and go’ type of power. It’s very important to me that I give practitioners the freedom and time to create as they wish. All interviews are sent back to the participants for oversight, and design choices are made collaboratively. While we usually work in serif fonts, we have had people specifically ask for sans serif. No problem. Due to our design language (and cost constraints), large amounts of white space are uncommon in Rat World. But sometimes breathing room is needed for a particular poem or photo series. All good. The publication is held by many hands.

I sometimes worry that Rat World doesn’t have a particular style, but it does: It’s a style created by us together.

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another book launch poster, 2024

Poster by Amber Clausner

Rat World is an object of collective effort and respect for artists. And I struggle to talk about ‘practice’ in relation to myself because of this very fact. Collective practice validates the artists you work with. It shows respect for their output and also challenges your own inherent creative biases.

But it also means that Rat World will always exist within the reality of people and place. I don’t know how long I will be in the arts scene and I don’t know what the future of Rat World is, but truthfully, all of that is irrelevant; Rat World is not just me. It is us all, and together we make it real. The connections and collaborations and learnings are real and they will continue to exist beyond Rat World. This magazine was never a long-planned, critically proposed arts concept. It wasn’t even expected to go beyond one issue. This magazine was a late-night frenzy of Doing. It was born out of uncomfortable experiences at arts events, realisations that everyone seemed to know each other, anger that I was always on the outside of conversations. Do we have to use words like ‘ontological’ all the damned time? When I hear these strange, useless discussions about the arts, I think of my paternal grandfather, illiterate and trying to survive, dreaming of a better life for future generations. And I think of my dad saying that despite the poverty and the suffering, everyone helped each other.

Maybe I don’t really know what ‘practice’ means, but I do know that this publication is held by many hands and even if we stumble, we will never fall.